Alex Mar needed a love potion.

The man she’d been seeing had been derailed for weeks by frequent contact from an overwhelming ex; constant texts had him losing sleep. Mar was concerned about his emotional well-being, and, frankly, a little miffed that his attentions were divided. Most of us would handle this sort of romantic tumult by shrugging, leaving or seeking out therapy. The more conventionally religious of us might pray for peace of mind.

But Mar had been in the throes of researching a new book on the contemporary practice of witchcraft, and the many forms it takes on. She spent five years traveling across the country, spending time with covens in California and New Orleans, in an attempt to explain the forces that drive people toward Paganism, a lump of related religious movements that are practiced by as many as 1.2 million Americans (relative to the estimated 55,000 practicing Scientology).

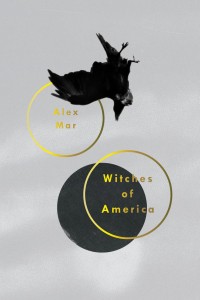

In the introduction to her newly published book, Witches of America, Mar writes, “There may be hundreds of strands of Paganism, but these super-esoteric paths share a clear core. They are polytheistic and nature-worshipping, and believe that female and male forces have equal sway in the universe. They teach that the divine can be found within us and all around us, and that we can communicate regularly with the dead and the gods without a priestly go-between.” Mar continues to list the qualities of witchy religions: recruitment isn’t generally practiced (a “calling” on the part of a potential initiate is considered much more powerful), and “good” and “evil” aren’t thought of as warring forces. Rather, they’re two sides of the same coin.

So, when Mar emailed her friend who practices witchcraft in the tradition of Feri for a love potion, she felt that her intentions were good. But, many Pagans would assert that there are broader, more “evil” implications surrounding the choice and how it will impact others. Without this very Christian spectrum to guide them as a moral compass, many Pagans operate under a creed as child-like and simple as “Do unto others … ” It goes: “An it harm none, do what thou wilt.”

It’s a spiritual movement focused on nature, equality, and the triumph of the self. Which is about as stereotypically American as a social practice can be.

This, of course, is at odds with how witches are portrayed in pop culture: menacing, destructive, manipulative. There are the overtly sinister, like Harry Potter‘s Bellatrix Lestrange or Fiona Goode in “American Horror Story,” but even the supposedly good witches in pop culture — Sabrina, Hermione — use their powers to influence others, playing little pranks to advocate for social justice.

And this is nothing new. Shakespeare’s “weyward Sisters,” the three witches who predict Macbeth’s demise, are shrouded in evil and mystery. And their origins date back to the ancient Grecian Fates. American lore surrounding the Salem Witch Trials, while generally accepted as unfounded, works to reinforce the idea that practicing witchcraft is, if not worthy of punishment, at least an activity for misfits and outsiders.

That last stereotype — that the label “witch” might as well read “outsider” — was the one most in line with Mar’s findings. Sure, she learned that modern-day witches do chant and cast spells. She learned that sex is a central tenet of certain traditions, one of which requires that a potential coven member orgasm to complete initiation. But these practices, contrary to popular perception, are mostly concerned with self-discovery, not casting spells on others. On her journey, Mar learned that witches are outsiders, partly because their religion is decidedly turned inward.

So, perhaps the most accurate portrayal of witchhood in popular culture is Cordelia Goode’s speech rounding out the Coven season of “American Horror Story.” She asserts that her coven is not a cult; that they don’t proselytize. Instead, they appreciate taking in students who feel being a witch is a calling — she supports those who approach her, not vice versa.

Which is why Mar’s book — initially an anthropological study, but one that recedes behind a personal hunt for spiritual fulfillment — is such an enlightening read. After befriending a high priestess name Morpheus whom she exchanges emails with and visits in person, Mar’s interest in Paganism spiked. As an ex-Catholic who struggles to express herself, she finds that partaking in chanting rituals makes her feel airy and empowered.

So, she confesses that partway through her research, her journalistic interests might’ve become fuddled with her personal interests. She begins dabbling in witchhood herself, visiting a few covens before deciding on one she could imagine herself belonging to.

One coven she doesn’t quite jive with is a Dianic sect that gathers in rural Illinois to ritualistically chant second-wave feminist creeds such as, “My body is the body of the Goddess.” Although Mar admires the fervor of this sect, she finds the language they use antiquated. Many such offshoots of Paganism rose along with the feminist movement, founding a more equal alternative to more traditional, patriarchal religions. It is perhaps the most political and social of the groups Mar visited — a gathering might involve chanting mantras along the lines of, “Justice for our sisters!” — which is partly why she abandoned it for the more self-focused arms of witchhood.

Another tradition Mar explores is Feri, a sensual religion centered on the concept that each individual has three souls — much like the id, ego and superego. Spells and other practices focus on ensuring that the three souls are properly aligned. So, while she’s an initiate, Mar vigorously cleans her apartment and partakes in rituals in her own home, such as rolling an egg across her back before chucking it into the sink.

She also pays a priestess named Karina roughly the same price as a monthly cell phone bill for training via Skype. Karina reiterates again and again that much of Mar’s training will involve unearthing suppressed issues and desires — much like in therapy. And when Mar questions her place in the coven, her teacher responds, “Whether you’re a witch or not — that’s something I would never, never answer for anyone.”

Though Mar may not necessarily resolve this question for herself, she does provide illuminating answers about what witchcraft in America means today: It’s a spiritual movement focused on nature, equality and the triumph of the self. Which is about as stereotypically American as a social practice can be.