Social media has become a powerful tool for organizing protests but also attracts law enforcement scrutiny. Black Lives Matter protests, like the one at the Mall of America, show its dual role in advocacy and surveillance. This article examines how monitoring peaceful activism affects privacy, free speech, and democracy.

On Dec. 23, 2015, on one of the busiest shopping days of the holiday season, the Minneapolis chapter of Black Lives Matter staged a protest at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota, to demand justice for Jamar Clark, an unarmed 24-year-old black man fatally shot by Minneapolis police. According to ABC News, around 80 stores in the mall were closed for an hour while police escorted protesters from the building.

Days before the planned protest, after the group used Facebook and Twitter to promote it, the mall had attempted to secure a temporary restraining order. While Hennepin County District Court Judge Karen Janisch did not grant the restraining order — or a request that the group post a cancellation notice on its Facebook event page — she agreed to bar three of the organizers cited as defendants in the mall’s petition.

It wasn’t the first time that Black Lives Matter Minneapolis had occupied the Mall of America — or that social media played a pivotal role. Months after the group’s Dec. 20, 2014, “die in,” the Intercept reported the mall’s security team had used social media to monitor the group, even creating a fake Facebook profile to “Like” the Black Lives Matter Minneapolis Facebook page and view the profiles of specific activists.

If the idea of a private security outfit stalking demonstrably peaceful activists on social media creeps you out, recent revelations that local, state and federal law enforcement divisions may have been using social media tools to keep tabs on Black Lives Matter activists won’t make you feel any better.

While this kind of monitoring may not violate any privacy laws given the public nature of social media, the practice raises troubling questions about why law enforcement is targeting individuals who are engaging in constitutionally protected activities and how a technology that empowers citizens to exercise their freedom of speech may also be used to undermine it.

You have new followers: Police-monitoring of social media is nothing new. But as Mic’s Jack Smith IV reported in November, it’s increasingly becoming an automated tool for predictive policing.

In recent months, investigations found law enforcement divisions in U.S. cities may have used social media to monitor Black Lives Matter. In November, Oregon Public Broadcasting reported that the Criminal Justice Division of the Oregon Department of Justice had been tracking people in the state using #BlackLivesMatter, among other hashtags, on social media. Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum said she was “outraged” to learn about the monitoring from the Urban League of Portland and ordered the searches of the hashtag to stop immediately. (Rosenblum further promised to hold an independent investigation of the department, hiring an outside attorney to conduct a thorough search that could go through June, according to Oregon Live.)

A month later, the American Civil Liberties Union revealed local law enforcement in Fresno, California, were also testing out surveillance software in their community. After an extensive public records request, Matt Cagle, ACLU of Northern California’s technology and civil liberties policy attorney, discovered the Fresno Police Department was experimenting with four social media monitoring software applications: Geofeedia, LifeRaft, Media Sonar and Beware.

In a solicitation email to Fresno police, Media Sonar’s co-founder sent a list of social media hashtags that could “help identify illegal activity and threats to public safety.” The list included a separate section for tags related to Michael Brown, the unarmed 18-year-old fatally shot by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, suggesting #BlackLivesMatter, #DontShoot and #ImUnarmed as search terms to track with the software.

Fresno police responded that their intention was not to track Black Lives Matter, but to monitor things like “violent crime and terrorism,” according to the Fresno Bee.

“If someone was threatening to bring a gun to a specific high school or mall, we could do a geofence (using Google Maps) and monitor for a gun or mass shooting,” Fresno Police Department Sgt. Steve Castro said. “To use it to monitor protest groups or demonstrations — that’s not our aim.”

The ACLU found no evidence Fresno police were specifically tracking Black Lives Matter related hashtags, but Cagle said the records they obtained “do raise questions about what software the police are currently using in the field and why they went forward without public involvement.”

Fresno police are also using a surveillance software called Beware that scans a name or address for all publicly available information online — including social media — and then assigns it a color-coded threat level: green, yellow or red. Police don’t know how the algorithm determines threat levels. Only the company that produces the software, Intrado, does.

City councilmembers and citizens are concerned the software could inaccurately rate someone based on what it determines threat-worthy. A local media report revealed that a woman’s threat level was elevated after tweeting about a card game called “Rage,” according to the Washington Post.

“Using social media to decide who is or isn’t a criminal,” Mic’s Smith wrote, “opens up the door for prejudicial police profiling.”If the police using the software aren’t even aware of what determines a certain threat level, it could create false assumptions about just how dangerous or threatening a person or place is.

Situational awareness: While these two instances occurred at the state and local level in smaller communities, the Intercept reported in July that the Department of Homeland Security has been tracking Black Lives Matter via social media monitoring and other forms of surveillance since protests began after Brown’s death.

According to DHS documents, the National Operating Center’s Social Media Monitoring and Situational Awareness program doesn’t collect information that identifies people specifically. A DHS spokesperson told Mother Jones that surveillance is limited to searching hashtags and keywords on social media sites to “ensure that critical information reaches appropriate decision-makers in federal, state, local, tribal and territorial governments.” Mic has reached out to the Department of Homeland Security for further clarification of its policy.

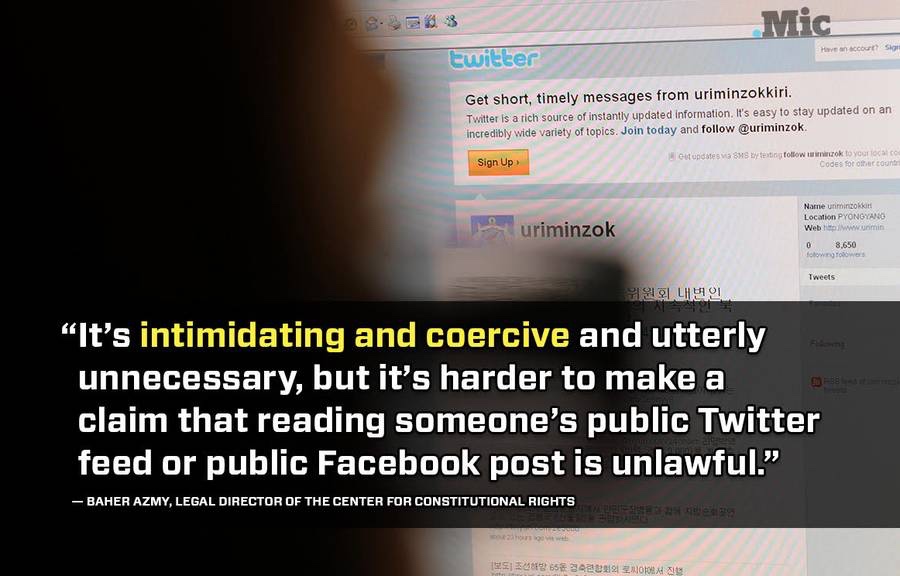

“If they are monitoring what is otherwise public, it’s OK,” Baher Azmy, legal director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, told Mic. “It’s still intimidating and coercive and utterly unnecessary, but it’s harder to make a claim that reading someone’s public Twitter feed or public Facebook post is unlawful.”

Echoes of Cointelpro: Unlike the National Security Administration’s sprawling, indiscriminate domestic surveillance program, exposed by Edward Snowden in 2013, the idea of police departments tracking your Twitter account is more of a throwback to the kind of surveillance typified by Cointelpro, an FBI initiative that tracked communists, anti-war protesters, ethnic minorities and cultural figures from the 1950s to the ’70s. The bureau notoriously kept files on civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Fred Hampton, as well as the political activities of cultural icons like Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck and Frank Sinatra.

With 21st-century digital technologies and open platforms, however, law enforcement divisions can amass much greater quantities of publicly available data on individuals than ever before.

“Today, in 2016, the capacity for information storage and dissemination by law enforcement agencies across the country is huge,” Nusrat Choudhury, staff attorney for the ACLU’s Racial Justice Program, told Mic. “This is because, post-9/11, we have seen the explosion of nationwide so-called ‘suspicious activity reporting’ systems, and these involve law enforcement agencies sharing with each other and with the federal government information that is supposedly deemed suspicious.”

“You internalize the fear of being surveilled so you self-censor or become more cautious.”

The chilling effect: As with the Oregon and Fresno cases, such monitoring of social media is not unlawful. But as the practice becomes more widespread, the chilling effect of knowing your social media activity is being watched could have real First Amendment implications.

“Federal, local and state law enforcement are allowed to go to public places where people are gathering,” Choudhury said. “They’re allowed to look at social media. The problem arises when this monitoring of people engaged in their First Amendment-protected protest activity chills their ability to express their views and engage in that protest. Then there’s a First Amendment problem. It can be hard to identify when that line is crossed.”

When people stop participating in a protest or even tweeting something about Black Lives Matter because they feel they might get flagged, that chill is “the big threat of surveillance,” according to Brendan McQuade, DePaul University visiting assistant professor of international studies. “You internalize the fear of being surveilled so you self-censor or become more cautious,” McQuade told Mic. “You think that there is this very powerful state monitoring you all the time.”

Organizer Allen Kwabena Frimpong is part of the Black Lives Matter Collective in New York City and the Malcolm X Grassroots movement. Although he has never confirmed he’s been singled out and tracked at any level of law enforcement, Frimpong expects that some amount of surveillance will follow his actions.

“The assumption for many organizers, especially here in New York City, is… that you are being put under surveillance,” Frimpong told Mic. “The right to peacefully assemble is not something that should create paranoia in one’s head.”

An open discussion about surveillance: To be sure, many law enforcement divisions are responsibly experimenting with surveillance technology. In 2013, 90% of police departments were using some type of surveillance according to information from the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported by the Washington Post. From Stingrays, which allow police to surveil all cellphone signals in a given area at once, to license plate readers, technology has the ability to make law enforcement more powerful and effective, if and when used properly.

But many of these technologies are so new that their effectiveness and impact are still undetermined. Problems arise when the public is unaware that these new, potentially invasive, technologies are being used.

“Social media monitoring, like all surveillance technologies, should never be adopted without meaningful public input and community oversight,” Cagle said. “It’s unacceptable when people are potentially labeled as threats to public safety simply for objections to police violence.”

There are ways to create an open dialogue about the new technologies law enforcement is using. Oakland, California, is one of the first communities to establish both a privacy policy and a committee to monitor and evaluate what kind of new surveillance technologies their local law enforcement is using.

The initiative was prompted when the Oakland Police Department and operations group running the port’s Domain Awareness Center, a surveillance complex, announced plans to invest $2 million in federal grant money to expand the center and its technologies to the entire city. In response, a group of residents formed the Oakland Privacy Working Group in opposition to the project.

“Oakland residents demanded more transparency and accountability from the elected leaders, and that resulted in real safeguards that were decided on by the public and put on this surveillance complex so that civil liberties and civil rights could be protected,” Cagle said.

In March 2014, the city council appointed an ad-hoc working group to create the first set of privacy guidelines for the center and its surveillance technologies. The policy was adopted June 2, 2015. The privacy working group has now become a constant presence on the city council to continue to evaluate these new tools as law enforcement adopts them.

“A lot of times, surveillance equipment is introduced, and we’re told it’s going to do one thing, but there’s no restrictions on use so it ends up getting used all the time for different things.”

“A lot of times, surveillance equipment is introduced, and we’re told it’s going to do one thing, but there’s no restriction on use so it ends up getting used all the time for different things,” Brian Hofer, a member of the Oakland privacy working group and chair of the Domain Awareness Center ad hoc privacy committee, told Mic. “They tell us a Stingray is to go catch terrorists, but then you find out that people have used it for petty theft or to recover a stolen phone or laptop.”

Since the working group formed, Hofer has noticed a change in the conversation around surveillance in their community.

“We went from not getting listened to at all and just going full speed ahead with this Domain Awareness Center to suddenly getting a unanimous vote for a standing privacy committee,” Hofer said. “I think City Hall has really acknowledged that there is a privacy impact from the use of surveillance equipment. Law enforcement included has realized that we need to think before we act.”

Such open dialogue and awareness about surveillance technology is critical, says Cagle, of the ACLU. “Surveillance and surveillance equipment in the hands of police risks targeting communities that are already vulnerable to police misconduct,” he said. “That’s why it’s so essential for there to be safeguards that guarantee transparency, oversight and accountability for the use of all surveillance technology, and those safeguards are essential to protecting civil liberties.”

Given how important social media has been to the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, the notion that law enforcement’s use of the technology may undermine their message is especially troubling to the ACLU’s Choudhury.

“Protests and dissent are critical to progress and issues of social justice in this country,” she said. “And at this time, when the issue of black lives and racial justice is finally getting the attention it deserves, is the absolute worst time to stamp out that dissent and protest by surveilling peaceful protesters.”

Editor’s Note: To learn more about the surveillance of social media, check out this video.

This branded content story is presented in collaboration with Truth and Power, a new investigative documentary TV series on Pivot that tells the stories of ordinary people going to extraordinary lengths to expose breaches of public trust by private institutions and governments. Watch all-new episodes of Truth and Power every Friday at 10 p.m. ET / PT, only on Pivot. For more information about Mic’s branded content guidelines, please visit our FAQ page.

written by Ellie Kaufman for Tech.Mic.