by Jubrin Danbaba

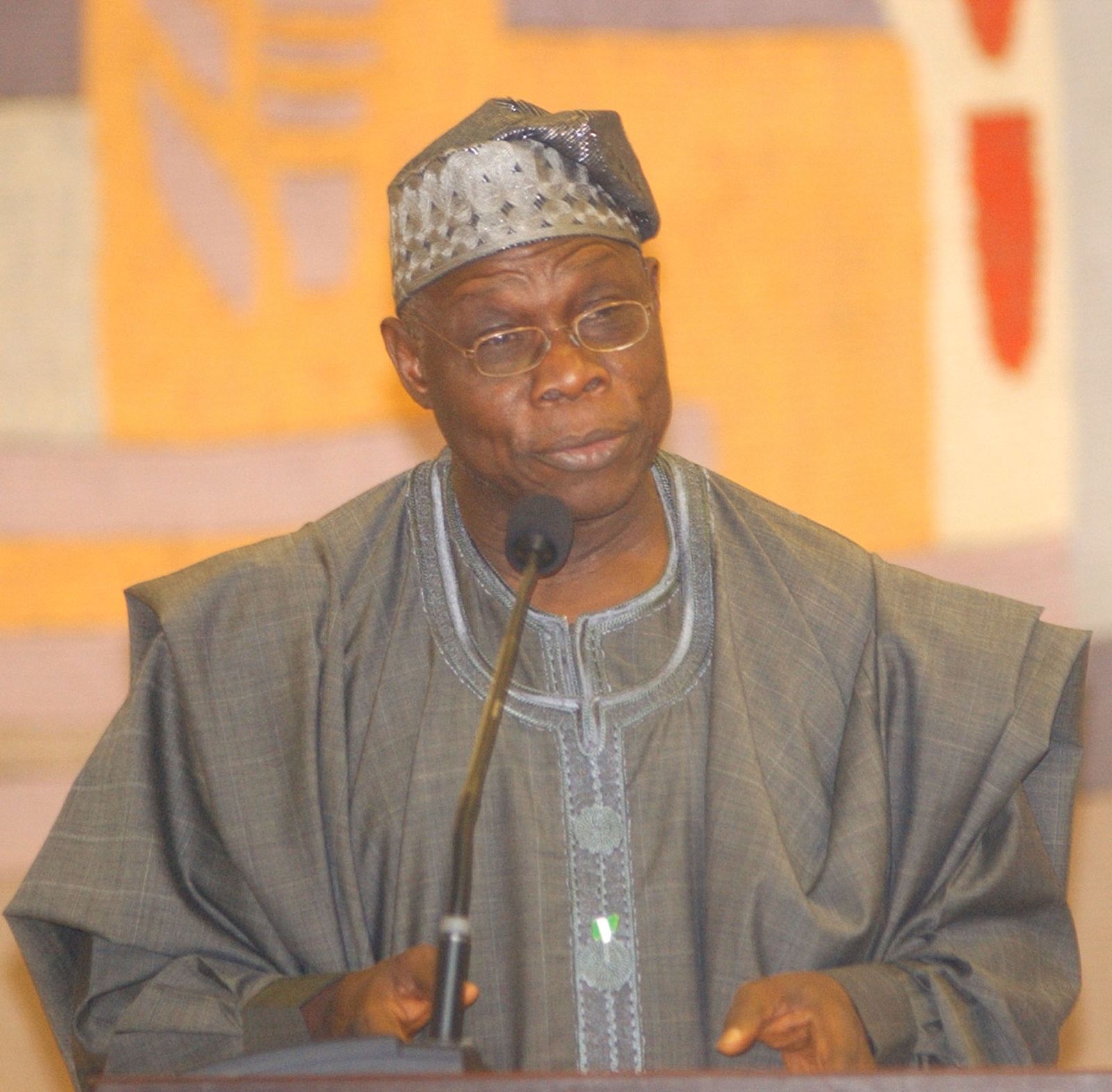

The problem with Olusegun Obasanjo is that his previous words and deeds persistently argue for his loss of that essentially moral right to critique even during times of critical situations. For Obasanjo, it is always easier said than done. Before he came to power in 1999, Obasanjo laboured tirelessly to fault governments that couldn’t make fuel available in petrol stations around the country citing Nigeria’s global position as a leading petroleum producer. But Obasanjo came, spent 8 years as president, and left longer queues for fuel at the petrol stations: he was worse than those he castigated.

Much later after he had left office, Obasanjo reprimanded the Central Bank of Nigeria for nursing the prospects of a 5000 naira note saying the introduction of higher naira denominations causes nothing but inflation. But while in power, Obasanjo introduced more denominations than any president in Nigeria’s history: 100, 200, 500 naira notes respectively.

At his last breakfast in the Presidential Villa on May 29, 2007, Obasanjo vowed to control Aso Rock from his own Ota farm. Ever since this control proved impossible—with Umaru Yar’Adua and now with Goodluck Jonathan—Obasanjo never relented in using every moment of political crisis in the country to his advantage; reminding us how good a Samaritan he was to the country during his rule, and how, the country stinks now that he left its helms.

The same frustrations that Obasanjo is complaining of due to the pains meted out upon him by the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) today—thanks to Jonathan—had been inflicted upon others by Obasanjo. Obasanjo would frustrate and punish anyone who took the liberty to dare him. He replaced PDP chairmen as well as senate presidents at will, and made sure that the party no longer provided that level playing ground where its members could foster their political ambitions without threats and intimidation.

When his infamous Third Term bid failed, Obasanjo decided to punish Nigerians—apologies to Okey Ndibe—by imposing a terminally ill president and clueless vice president upon the country. He thus played a direct role in seeing to the actualisation of all the wrongs of Nigeria ever since her return to democracy in 1999. He may tear away his membership card of that behemoth party, but he can’t tear away his guilt; which we all know and recount with discontentment.

But those who defend Obasanjo now tell us that “no human being is perfect/we all have faults” in order to promote their arguments at the peril of other issues. In my engagements, I don’t adopt this human-imperfection theory because although it is logical on the one-hand, there is an illogic that follows it on the other-hand. If we dismiss Obasanjo’s past and present misbehaviours as evidence of the fact that no human being is perfect, then we will have to lend the same gesture to Jonathan, whom we seek to vilify, since he (Jonathan) too, is a human being who is not perfect. A further problem that the use of this theory elicits is that irrespective of the magnitude of the crime committed, all human beings can be pardoned for simply being innately imperfect; no one (including Obasanjo, Jonathan and everyone) can be found guilty under this edict.

The second issue is that of the belief that there comes a day when a bad person resolves to do well, and when that day is here, we should simply forget the bad past, and judge such bad people by looking at their present. Well, this one is really baffling in the sense that all too soon, we have forgotten the terms upon which forgiveness must be granted, whether divine or earthly. The fact is that Obasanjo is not asking (and has never asked) for forgiveness. Obasanjo is simply a failed leader who took it upon himself to control the affairs of his country even after he left office.

He came to office poor and miserable but left in stupendous wealth—apologies to Wikileaks. For him to be forgiven and be accepted as a fighter for the cause of the masses, he will need to go beyond tearing his PDP membership card. He will need to ‘tear’ all his ill-gotten assets by returning his loot to its rightful coffers, then come back and ask Nigerians for forgiveness. If Obasanjo doesn’t do this, he has not shown remorse that is expected from a person seeking forgiveness; but his actions and inactions both in words and in deeds only tell us that his circumstance of leaving the PDP is one that was borne from personal differences with Jonathan rather than patriotism for Nigeria.

In the final analysis, I accept that Jonathan has failed miserably, and my criticism of Obasanjo is not to be mistaken for an endorsement of Jonathan. We should see Jonathan’s failures (and work toward voting him out) with or without Obasanjo’s stagy, ostentatious, over-the-top, dramaturgical balderdash; no amount of his animus for Jonathan should beatify him. Jonathan should therefore be criticised, but he shouldn’t be criticised because Obasanjo tells us or wants us to do so. Obasanjo doesn’t need the attention of any serious Nigerian.

Jubrin Danbaba is a freelance writer

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.