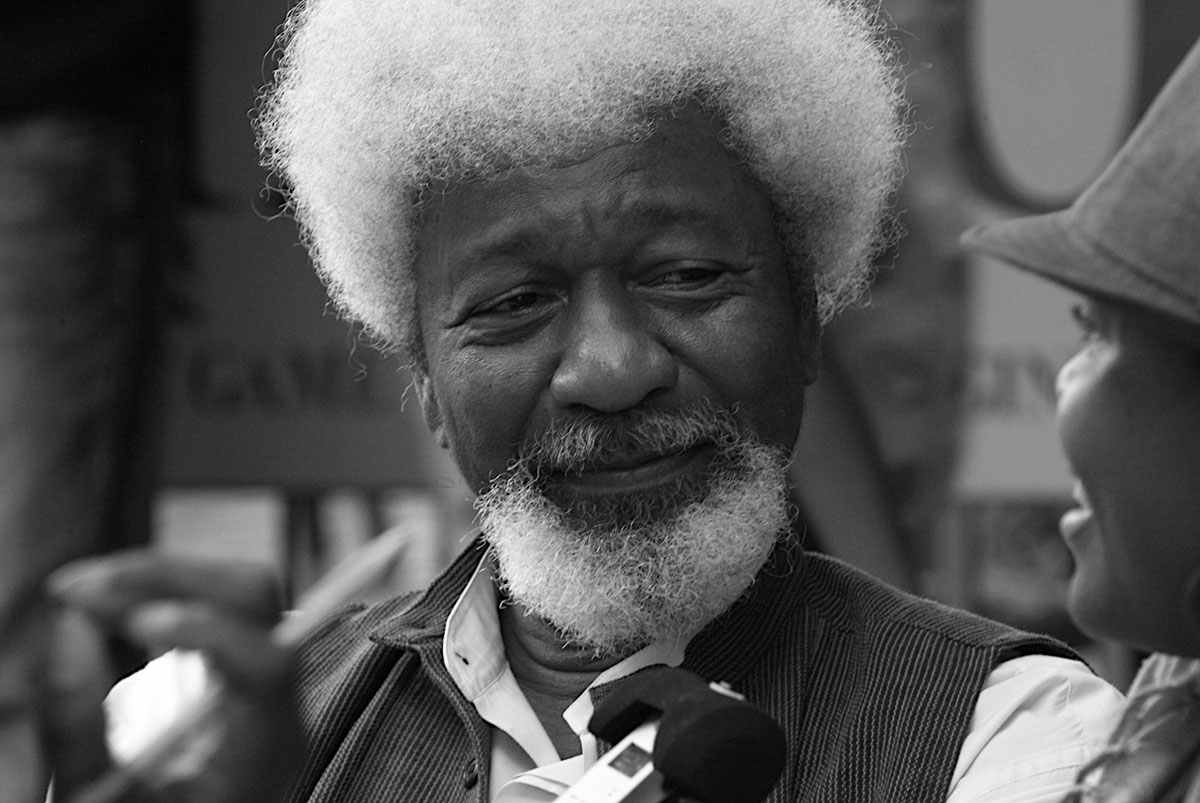

Years ago, on a certain Sunday night, around 9.15pm, I was snoring away in my bed, sleeping soundly, maybe, when my father woke up: “Wole Soyinka is on NTA!” My eyes just cleared immediately. I ran out of the room and sat, beery-eyed before the TV and watched as the man in beautiful white hair read poems with a musical background to it. My father kept looking at me and he could sense the joy that engulfed me each time we talked about Wole Soyinka, read about him or even saw him on TV. My father had newspaper clips of Wole Soyinka, saved for me.

“Fairytales do come true”, Frank Sinatra sang,” it could happen to you”.

Fastforward to when I was 16 years old, during the 70th birthday anniversary of the Nobel Laureate, I was on a night bus, in a rickety Ifesinachi boss, coming to Lagos, for the first time in my life, to be part of the Wole Soyinka Festival. Before I got onto that bus, my father had cursed the nonsense out of my life. How could you risk your life like that? He refused to give me a penny. My mother gave me money and said, “Onyi, go. Be safe! Find what you are looking for!” This might sound a bit homo-erotic, but I was looking for Wole Soyinka. I think my father was just jealous; that was why he tried to stop me. Sometimes, you don’t stop people when they have made up their minds on some things. That bus journey was scary. I arrived the city of madness, stressed, exhausted, but completely excited.

Before I got onto that bus, I had been communicating with a certain man called Professor Femi Osofisan. He was in charge of the National Theatre in Iganmu then and that was where this event was taking place to celebrate Wole Soyinka. As soon as I got to my aunt’s house in Okota, on the next day, I found my way to the National Theatre to find that man. I sat for a long time in his office, because I came very early. I didn’t even tell him I was coming. When he walked in, I knew he was the one. I stood up, greeted him and he was full of smiles. I didn’t tell him I was the one bombarding his email box. He went into his office and his secretary quickly went in and told him I was waiting for him. He asked me to come in, “Are you Onyeka?” He asked me. I nodded, shivering, because I had read almost everything he wrote. His essays, his poetry and his plays. And the ones he even wrote in newspapers with pen names. I froze. Dreams come true, I said to myself. He asked me to sit down and said he would send me to another man called Jahman Anikulapo. My heart started racing. Fast. This was my first time in Lagos and all these Yoruba people are just kind to me like this, I kept thinking.

That afternoon, after he bought me lunch and gave me money, Professor Osofisan introduced me to Jahman Anikulapo. Jahman quickly left everything he was doing and paid attention to me. It was the first time I was seeing Joke Silva in person; she was clapping and smiling at me when I read a poem I had written for Wole Soyinka. I know; everything I did was childish: my presentation and how naive I thought people in Lagos were. They were all childish, but they accepted me.

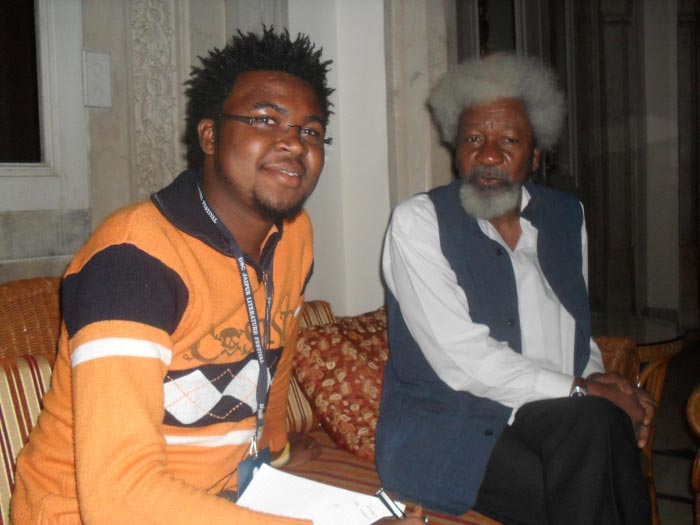

I met Wole Soyinka finally at night, inside Jazzville in Onike, Yaba. He had come for a poetry reading organised in his honour. It was the first time I almost fainted because I saw a human being I loved. We stood there on the podium and camera flashlights engulfed the whole place. He held me on the shoulder for some minutes and I felt all my problems had come to an end.

Life has never been easy, but reading about the life of Wole Soyinka, on everything he’s been through, I’ve got much power to move on. I have never really thought that I would some day achieve some of the things I dreamed of achieving, but with the thought of Wole Soyinka conquering the entire universe, I’ve been able to swirl all through the world in pride.

After the publication of my first novel, The Abyssinian Boy, I travelled to India with my publishers and we were going to ‘hang out’ with Wole Soyinka. We were not surprised that he was mobbed by the Indian media, so getting to him at his hotel was very difficult. He was not available at all. I thought of what to do and then slipped a note underneath the door of his hotel, with my name on it. When we returned, the receptionists ran to us and said the Nobel Laureate had tried calling us and that he was waiting for us at the lobby. We went there and he politely discharged all the people who wanted his attention and sat with us for hours, talking to us, having the conversation taped by my publisher, Ayodele Arigbabu. He narrated his experience travelling to St. Lucia for the 80th birthday of his colleague, Dereck Walcott. He said:

“Let me tell you what happened on my way here to give you an idea. I went to St. Lucia for the 80th birthday of my colleague- Derek Walcott, the Caribbean writer. I went to deliver the keynote address at what they called the Nobel Laureate Week in St. Lucia and my flight took me via San Juan in Puerto Rico to re-enter the United States. And there I was pulled aside! When I came through the immigration, they looked at my passport, saw I was Nigerian, asked me all sorts of questions, I answered them. So I was told to go for what they called a secondary check. So I had to sit there with illegal immigrants or suspect immigrants or whatever….just a few days ago, on my way here. I must have been kept there for 20- 25 minutes – I nearly missed my connection – and eventually I was called to the desk and I was not asked one single question. The man smiled, he just asked a perfunctory thing…”how long are you staying? Okay, do have a nice stay”. He did not ask me one single security question and gave me back my passport, they all smiled and so on. So I said, is that what we, who carry this passport now have to undergo every time? I said, you haven’t asked me any question but obviously, you’ve been making enquiries. He just smiled an apologetic smile. So this is what this passport now means. This was just a few days ago. So the problem is not trivial at all and I can imagine that’s happened to me, I can imagine it’s happening to hundreds of other Nigerians.”

That night I gave Soyinka a copy of The Abyssinian Boy, which he read and emailed me, encouraging me to write more.

As a child growing up, I was overly obsessed with Wole Soyinka and his coinage of words; he made the English language so beautiful that I felt he created that particular language. I was fascinated by verbose and bombastic expressions, especially made in his writings. He played on words, he derived joy in conjuring up words to make things seem very comical. That was his power. Honestly, I didn’t make any sense of what I read, but I enjoyed the construction of the sentences. JP Clark’s Wives Revolt and Wole Soyinka’s The Lion and the Jewel made me bubble back then. I could read them again and again and yet, I didn’t understand what these characters who are commoners said. I also read poems by these geniuses without understanding them. I was told that a genius is someone from hell who is from hell who is never understood.

Intellectually, Wole Soyinka has influenced me. Radically, he has twisted my mind. Personally, he has saved my soul. Just earlier this year, I got into a big problem at one of the foreign embassies in Lagos. I tried many ways to resolve the issue. It was difficult. I made up my mind and emailed the Nobel Laureate, honestly explaining the situation I found myself in. And quickly, as usual, he replied: “Oh dear, that’s a great pity. However, I’ll see what I can do. I return home in about a fortnight and will have a word with him.” That problem was solved once he got back! He kept to his promise.

And I bounced back. And I am happy that he is alive watching over those of us who revere and love him. I am happy he’s 80 years. I am happy that he is very strong and still speaking out against inhumanity!

Onyeka Nwelue is award-winning author of The Abyssinian Boy (DADA Books, 2009) and Burnt (Hattus, 2014). He’s currently Professor of African Studies and Literature at Instituto d’Amicis, Puebla in Mexico.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.