[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1992, Bill Clinton, then the Democratic Party candidate for the US presidency, popularized the phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid.” A year earlier, then incumbent President George H. Bush—who was seeking reelection on the platform of the Republican Party—had a high job approval rating on the strength of ordering a military offensive that drove invading Iraqi soldiers out of Kuwait. But by the time 1992 rolled around, much of Mr. Bush’s political capital had been eroded in the face of an incipient recession.

It was in this context that the Clinton campaign refined the devastating phrase: It’s the economy, stupid. The whole idea was to keep American voters focused, not on Mr. Clinton’s inexperience in foreign policy, not on the whiff of scandal that attached to the Democratic candidate because of his notoriety as a philanderer, but entirely on the bleak economy and rising layoffs that had affected many American families and left many others anxious about their future.

Mr. Clinton parlayed that expression and similar signs of economic disquiet into a winning political formula. The phrase became a devastatingly effective campaign slogan, a wave that enabled Mr. Clinton to dominate his opponent and to coast to the White House.

Nigeria is more than three years away from its next presidential election. President Muhammadu Buhari, who was sworn in last May, still has at least two years before he and his party should start worrying about reelection. Yet, the Nigerian president would do well to remember, last thing before going to bed and first thing on waking, “It’s economy, wise guy!” If need be, he should entrust one of his most dependable aides to remind him about this essential reality. Or if nobody cares for him fiercely enough to give him that chastening message, Mr. Buhari should devise a way to remind himself. It’s about the economy, man!

President Buhari should not look at the years that lie ahead before he or some other candidate of his ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) must ask Nigerians to approve another four years in presidential power. To look to the future is to surrender to the illusion that he and his party have time, lots of time. Instead, the president and his party should look at the nine months that have elapsed since Mr. Buhari’s inauguration. In that time, the Nigerian economy has gone terribly south and sour.

It should be stipulated that the tsunami of economic bad news was bound to hit our shores regardless of who won the election. Nigeria is facing the terrifying consequences of decades of irresponsible, visionless leadership. For decades, Nigerian “leaders” and their followers practiced a style of governance best described as eating and quaffing each day as if it would be the last. The more petro-dollars rolled into the Nigerian treasury, the more insatiable Nigerian officials became. Cursed with puny minds, they were incapable of realizing that they had in their grasp the resources to turn their country into a developmental showcase, the equivalent of those European, Asian and North American countries they regard as playgrounds. What Nigeria lacked was never the cash; it was always the will and the imagination.

Nigerians are witnessing the comeuppance for those decades of tragic squandermania. This is the culmination of all those years when a few Nigerians stole more than our country could afford, when the same few partied beyond our collective means. Yet, the Nigerian story can no longer be simplified as the recklessness of a few. Those who found ethnic or religious or clannish reasons to defend or hail the wasters of the country’s dreams bear part of the blame.

But let’s return to Buhari’s nine months in office. Regardless of whether he played a part in creating the current economic crisis, the reality is that it’s all come to a head under Mr. Buhari’s watch. Candidate Buhari had promised Nigerian voters that he was going to turn their country around. He never qualified his promises with the precondition that he must find a rosy economic picture—with soaring prices for crude oil and a lot of cash to play with. At any rate, if the circumstances had swung in a more fortunate direction and Nigeria’s economy began a boom phase a few months into his presidency, there’s no question Mr. Buhari would have claimed credit. After all, former President Goodluck Jonathan was quick to beat his chest when Nigeria surpassed South Africa to become Africa’s largest economy by GDP. This, even though the whole thing was achieved via a technical process, the re-basing of the Nigerian economy to account for the robust contributions made by the versatile entertainment industry and communications sector.

We should insist that it falls to Mr. Buhari to take a decisive lead in navigating Nigeria out of the perilous economic times. His body language, so far, does not inspire confidence that he recognizes the scale of the crisis or knows exactly what to do. The worsening foreign exchange has come to epitomize (for many Nigerians) the depth of the crisis. On an almost daily basis, I receive phone calls from friends and relatives who bemoan the misfortunes of the fast declining naira.

I’d suggest, however, that the drama of the slipping naira and the soaring dollar often obscures the deeper, more biting effect of the ongoing crisis. It lies in the reality and prospect of massive job losses and the possible closure of businesses across all sectors of the economy. Last week, a friend told me that her home state had laid off all contract staff. The same week, a business executive visiting the US disclosed that he knew some companies that had sent home one-third of their employees—and were on the verge of making more cuts.

Nigeria’s unemployment rates are unsustainably high to begin with. It’s not as if one could be fired from one company and then take a few steps down the street to get hired by another firm. Jobs are as difficult to come by in Nigeria as a jackpot in a Las Vegas casino. And that was true even before the current darkening climate.

Each employed Nigerian is often saddled with providing for many dependents. Each lost job has more multiplier implications than, say, a similar loss in the US or the UK. How are all the new jobless and their dependents going to eat, to clothe themselves, to pay their rents, to pay for medical treatment, etc, etc?

Even if the situation were not as grave, I doubt that Mr. Buhari’s economic team is as strong as it should be. Has the president what it takes to steer the economy, in the short run, out of the current storm, and, in the long run, to put it on a course of steady growth? Has he received the best advice on the nature and impact of the economic mess as well as possible panaceas?

One often wonders whether the president is a careful, patient listener, or is possessed of the mindset—notoriously exhibited by former President Olusegun Obasanjo—that he is all-knowing, beyond counsel.

Two weeks ago, Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka proposed that the president call an economic conference in order to generate expert advice on how best to tackle Nigeria’s foundering economy. One hopes that there’s truth to a recent newspaper report that Mr. Buhari was going to invite the country’s best economic minds to weigh in on the way forward.

Above all, the president should assure Nigerians that he reckons that, when it’s all well and done, it’s about the economy. Period!

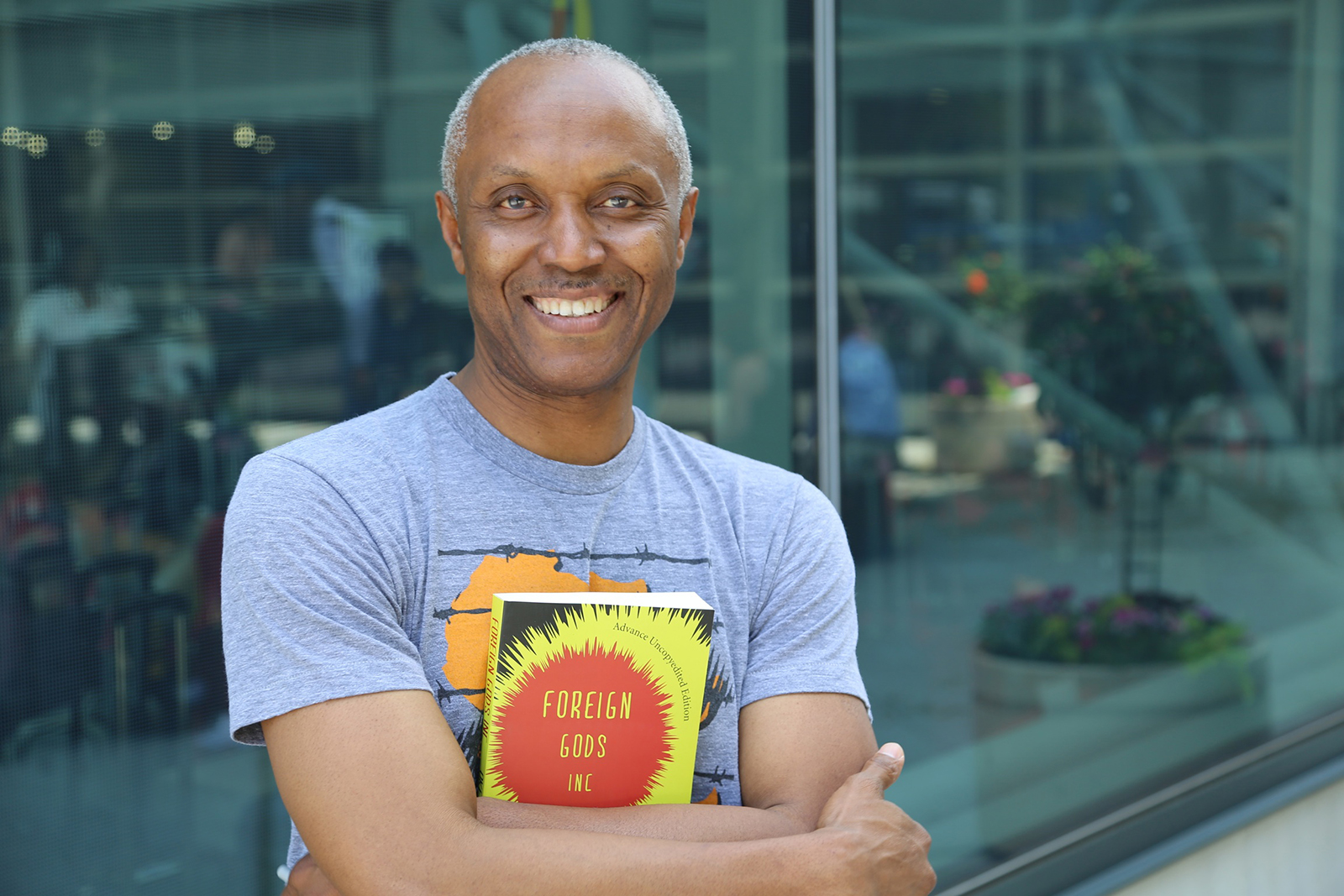

Okey Ndibe novelist, political columnist, and essayist. He teaches fiction and African literature at Trinity College in Hartford, USA. He is the author of the novels, Arrows of Rain and Foreign Gods Inc. He tweets from @okeyndibe.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.