[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he problem with Nigeria is the problem with the Niger Delta: bad governance, weak institutions, inequity, impunity, and more. One of the major differentiating factors between the national situation and the regional case is that the Niger Delta’s condition is gravely worsened by the continual ecological catastrophe that the Nigerian oil industry, led by major multinational corporations like Shell and Agip and Chevron, has inflicted on the region. At the risk of sounding alarmist, it must be sounded loudly that the raging environmental terrorism in the Niger Delta ranks with the ravages of Boko Haram in depravity. We still wonder, as suggested by one of our brightest activists, if our Oronto was not a victim of the carcinogenic agency of the oil industry.

This ecocide and the associated expropriation of ancient land and mineral rights by the colonial British crown and its successor Nigerian State have not only degraded the delicate terrain of the Delta region, but also deal the greatest combined assault on human security in the mostly coastal communities in the area. For dwellers in the Delta, the fabric is sucked out from their fundamental human rights to life, livelihood, ownership and enjoyment of property, human dignity and cultural identity, by the twin evils of constant petroleum pollution and confiscation of their native property rights.

This could not have been the prognosis for another twenty years since the “judicial” killing of the Ogoni poet and indigenous rights activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and seventeen years after the Operation Climate Change cum Kaiama Declaration launched by Oronto Douglas, Felix Tuodolo and their compatriots under the umbrella of the Ijaw Youths Council.

Over the last seventy-odd years, the Niger Delta has posted a rich history of social and political struggles, with each epoch having its fitting poster faces, starting with Ernest Ikoli, the veteran journalist who lies in the pantheon of nationalists like Nnamdi Azikiwe, Herbert Macauley and Obafemi Awolowo, that fought in the 40s-50s for Nigerian political independence. The venerated Harold Dappa-Biriye led the Niger Delta minorities’ advocacy for self-determination at the pre-independence Constitutional Conferences in London. Major Isaac Adaka Boro launched in 1966 the first recorded rebellion against independent Nigeria, declaring the Niger Delta Republic from Kaiama town in that twelve day war.

After the Nigerian Civil War ended in 1970, the Head of State, General Yakubu Gowon, skillfully inaugurated a period of national rapprochement tagged “Reconciliation, Reconstruction and Rehabilitation” (with the sobriquet of The 3-Rs). Smarting from that war and perhaps temporarily tempered by the conciliatory ambience of the 3-Rs programme, ethnic and regional struggles seem to have been less characterized by militancy and more by subtle to later vigorous political negotiation in the 1970s to 80s. The issues were more visibly contested in the 1978 Nigerian Constituent Assembly, that produced a draft of the eventual 1979 Constitution for the General Obasanjo military administration’s review, modification and approval. Ditto in the other military fostered political-constitutional conferences that held in the 1978 Nigerian Constituent Assembly, that produced a draft of the eventual 1979 Constitution for the General Obasanjo military administration’s review, modification and approval. Ditto in the other military fostered political-constitutional conferences that held in the 1980s and 90s under Generals Babangida and Abacha respectively. But there was a wide gulf in the balance of political bargaining power between the contending groups, with the Niger Delta and other minorities far outweighed in the numerical, military and economic indices of the real politik of the day.

Underwriting and accentuating this imbalance were the multinational oil companies who served as the Joint Venture operator-partner to the skewed Nigerian State in the oilfields of the Niger Delta, pumping out petrodollars into the national coffers, fabulously enriching other groups mostly outside the Delta through a corrupt and inequitable quasi-national patronage machinery, and leaving only blood, tears, poverty and pollution in the host communities bordering the Atlantic Ocean.

It was in this setting that tensions started to simmer and tempers began to rise again in the region, from the late 1980s. The Ogonis took the challenge and set an example in organized activism. Led by the Kobanis, Baadoms, Ledum Mitees and Orages, and with Ken Saro-Wiwa as spokesman, the Ogoni people combined community mobilization and intellectual advocacy in taking their environmental travails onto the global stage. Sharp internal divisions were later to take a costly toll on the Ogoni campwa as spokesman, the Ogoni people combined community mobilization and intellectual advocacy in taking their environmental travails onto the global stage. Sharp internal divisions were later to take a costly toll on the Ogoni campaign.

After the then Nigerian military government cruelly disposed of Ken and his colleagues and carried out a murderous pacification campaign in Ogoni land, with Major Paul Okuntimo as its notorious arrowhead, it was imaginable that it would thenceforth be all quiet on the Niger Delta front. Rather, that repression inspired a breed of brave and articulate activists and militants from the neighbouring Ijaw territory who decided, as one of the resultant militant groups would later be named, that Enough is Enough in the Niger Delta.

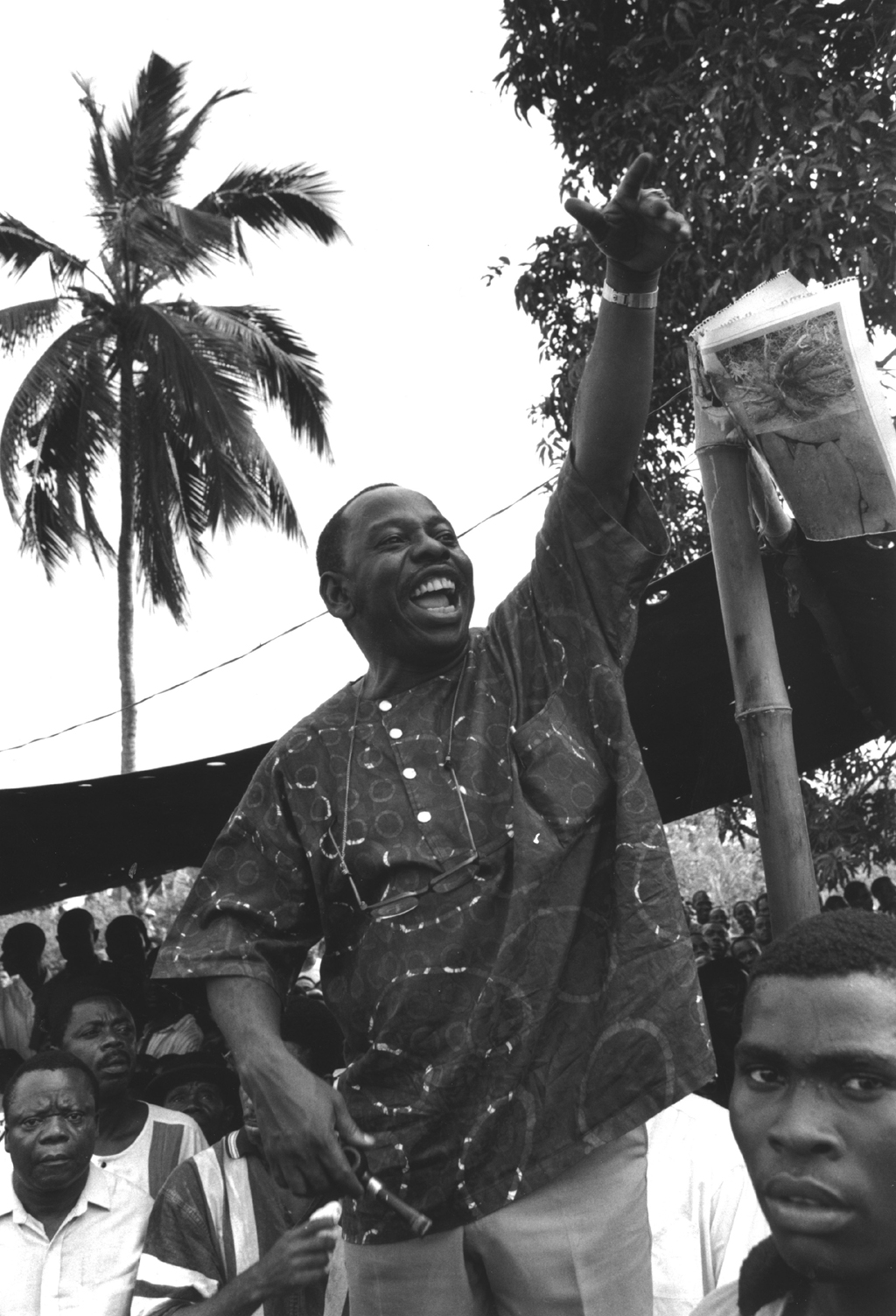

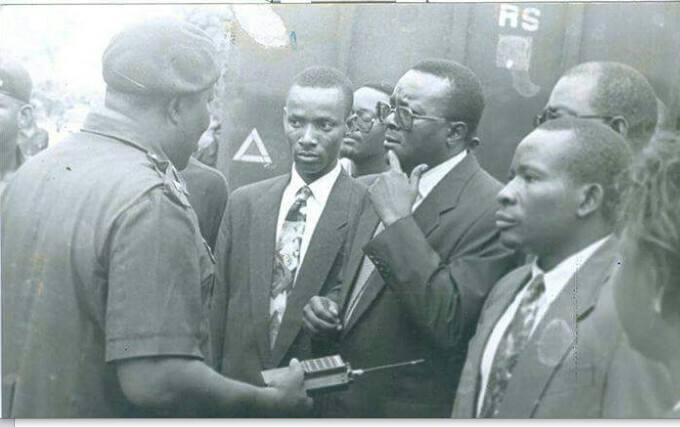

Enter Oronto Natei Douglas, Isaac “Sankara” Osuoka, Felix Tuodolo, Annie Brisibe, Emem Okon, Patterson Ogon, Von Kemedi, Asari Dokubo, Kingsley Kuku, Ann-Kio Briggs, the mythical “Jomo Gbomo” of MEND (Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta), Robert Aziboala, Joseph Evah (the guerrilla propagandist), Tompolo and many others, in no particular order. These are only some of the names that define the phase of the Niger Delta struggle when non-violent activism was at its most poignant and, as the voice of non-violent reason went unheeded, violent militancy took over, paradoxically, almost in seamless lockstep.

Not yet Uhuru, But … Is the Fault in Our Stars or in Us?

No, it is not yet Uhuru. The Niger Delta struggle within the Nigerian polity for restoration of ownership and control of natural resources, for authentic fiscal or economic federalism, for internal political self determination, for environmental justice and protection, and for respect for local communities has not quite been won. But there have been piecemeal palliatives and successes.

Just as Dappa-Biriye, Isaac Boro, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Oronto, Asari Dokubo and Tompolo have been sample faces of the various phases, the struggle has respectively been marked by milestones of dividends for which the region has those sets and generations of activists and militants to thank, despite the warts and collateral damage in the case of the latter. The milestones range from the Niger Delta Basin Development Board, the initial creation of states for minorities (Rivers, South Eastern and Midwestern States), the Oil Mineral Producing Areas Development Commission, accrual of 13% of the proceeds of petroleum production, the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), Federal Ministry of Niger Delta Affairs, the Niger Delta Amnesty Programme, the Nigerian Content Development and Monitoring Board – a.k.a. Local Content Board, to the United Nations (UNEP) Environmental Assessment of Ogoniland.

Of all the milestones though, the most celebrated and yet most transient concession to the Niger Delta struggle was the five-year presidency of Nigeria by an indigene of the Niger Delta, Dr. Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, commonly called “GEJ”, a stint that ended barely four months ago.

The big inconvenient question though, to borrow from a biblical context, is this: how has the Niger Delta as an organized geopolitical collectivity, assuming it is one, used its talents? It is a thorny question that has evoked a wide, yet low intensity, debate in sitting rooms and taverns in the Delta, but is probably still considered too sensitive for any deep or detached interrogation within the region, especially in relation to the period of GEJ’s Presidency.

There can be no doubt that with all these milestones have come some social and economic gains: roads, schools/universities, millionaires and more cars on the roads. But many commentators consider these to be merely incremental at best, and at worst too insignificant to count for any net value. Since 2000 when President Obasanjo belatedly and reluctantly started to release the 13% “Derivation” funds to oil producing states, those monies running into billions of dollars annually for each such state have for the most part (barring of course the odd exception) been mismanaged and misappropriated by state governors and their political apparatchiks, some of them massively rigged into office. Communities and the general populace only see trickles of the so-called dividends of democracy.

During the reign of one of the early civilian governors in Rivers State, many rural rigged into office. Communities and the general populace only see trickles of the so-called dividends of democracy. During the reign of one of the early civilian governors in Rivers State, many rural women could only taste tokens of such dividends – by way of wrappers and N10,000 stipends (less than £50 equivalent) – when they came out to line up as cheerleaders along the entrance to Government House, the Governor’s official residence, to show how much popular support the Governor enjoyed.

Some state officials, who were prosecuted for purloining public funds cried out, egged on by large fan clubs, that they were being persecuted for being champions of the resource control struggle. One of such guys is currently serving time in the UK, after escaping Nigeria’s weak justice institutions. There was no overriding counter narrative from the creeks, unmindful of the maxim that he who comes to equity must come with clean hands.

The NDDC is funded far less than its enabling statute requires the national government to do. Still, its receipts since its creation fifteen years ago are substantial, averaging over the last five years roughly a billion Pounds Sterling per annum. It has executed thousands of projects across the region, many of which are quite useful, and it may have done “better” than some dismally performing state governments. But the agency has gained notoriety as a contract-awarding patronage machine, rather than distinguish itself as a transformative development agency with any coordinated implementation of its intervention mandate, for optimal impact in a region in dire need of a visionary quantum leap. Through progressive degeneration in corporate governance and the quality of successive managements, there has recently emerged such a mismatch between its contractual obligations and its liquidity – approaching a trillion Naira (about three billion Pounds Sterling) – that it would have been taken over by AMCON, the body set up to absorb failed banks and their toxic loans – if NDDC were a bank.

The Presidential Amnesty Programme for the Niger Delta succeeded in retrieving militant agitators from the creeks and thereby saved Nigeria’s petroleum production from imminent collapse, having dropped to about 700,000 barrels per day from about two million. It has also sent teeming numbers of youths to schools and skills centres, including a generous number in foreign institutions. Impressive as this is, it is again not clear here if the managers of the programme did the rigorous, joined-up planning and institutional synergy that would have delivered maximum, creative and strategic value for money, rather than the usual consumptive pattern of public expenditure in Nigeria that seeks to explain itself through the historical or book cost of goods and services consumed. Thus, there are now hordes of trained youths without jobs; oil production has since bounced back to above two million barrels per day but oil theft and pipeline vandalism in the creeks has shot up (with untold impact on the environment and rural dwellers), and the Amnesty Programme’s management continues to be ensconced in the far away national capital, Abuja, with no strategic shift in its thrust to the “new” clear and present danger in the creeks: pipeline vandalism by otherwise displaced and disenfranchised youths.

Through more recent years, in the euphoria of the Jonathan or “Niger Delta” Presidency, a critical part of the region’s political elite and activist community went on to become high office holders, contractors, men of perceived influence and access, and sheer cheerleaders. The by then globally famous struggle for resource control and environmental justice went on a quiet holiday, or so it seemed. Instead, the Petroleum Industry Bill submitted by the Presidency for enactment during the period expressly reaffirmed (and rather unnecessarily, as it is already stated in the country’s Constitution, despite questions about that document’s legitimacy) that the Federation owns all mineral resources in the country.

There was hardly a concerted effort, in response to the historic rarity of a minority man in the Presidential Villa, to articulate a constructive engagement on the age long demands of the Niger Delta people, in order to achieve long term mass impact. Neither was there even a remotely Robin Hood type attempt to inject newfound resources and influence into the intellectual side of the struggle. Nor indeed was there one to build a groundswell of the highest quality policy and intellectual support – certainly not sycophantic – that would forever set this Niger Delta Presidency apart as an epoch of excellence and an unmistakable departure from the mediocrity that marked virtually all previous national administrations. Niger Delta activism and its poster boys and girls gradually started to incur perceptions of venality and mundane entrepreneurialism.

One of two telling reproaches of that short era is the non-implementation of recommendations in the United Nations Environment Programme’s Environmental Assessment of Ogoniland, four years after it was submitted to the Federal Government in 2011, when GEJ had been elected to the Presidency in his own right. The other is that, somehow, just somehow, the Federal Government did not before the end of President Jonathan’s five years in office get to complete the rehabilitation of the East-West Road, the most important highway in the region, connecting the Delta by road to mainland Nigeria.

Another that may be easily missed is that in the unprecedented divestment of numerous oil acreages to Nigerian capitalists by the multinational oil and gas companies, started and maturing during the time of a Niger Delta woman as Petroleum Minister under the Jonathan Presidency, no strategy was conceived to carefully integrate host communities and states into the ownership structure of these mineral blocs. In the meantime, the same communities and states are at the receiving end of the harsh externalities of petroleum production.

In Bayelsa State alone, there have been well over a thousand oil spillages between January 2014 and now, and fourteen persons died in one oil pipeline fire last July. Going by the pattern, such fires and explosions can no longer be considered unforeseeable. And Nigerian governments generally do not care enough about the environment to fund environmental regulation and enforcement in any sensible way. The national regulator, NOSDRA, claims that it got just about N200 million, less than a million Pounds Sterling, in all of 2014. It is also based in Abuja, thousands of miles away from the communities where oil is produced and where oil spills need to be promptly responded to.

More probing observers might even go as far as pointing out that all of the major milestones listed in this note were initiated when Presidents from other parts of the country were in office, and none of them during the GEJ years. A profound, if subliminal, counter to that is that the ascendancy of President Jonathan into office placed an accent on the identity of the people(s) of the Niger Delta region.

This dividend is enriched by the fact that Jonathan also personifies in more unprecedented ways than one the greatest single leaps in the consolidation of democracy in Nigeria’s recent political history: the Obamaesque possibility of a minority rising to become Number One Citizen, and that historic congratulatory phone call he made to his victorious opponent, Muhammadu Buhari, who instinctively responded “my respect, Your Excellency”.

It is arguable that good governance was hitherto not woven into the overarching definition of the strong moral and socio-political cause of the Niger Delta people(s). We may also have forgotten another time tested maxim of equity: that equity aids the vigilant, not the indolent. What is not arguable is that there is need for a renewed narrative on the Niger Delta cause, that will be infused with all such moral elements as good governance, internal integrity and eternal vigilance. Old champions are genuinely needed still. But authentic fresh voices are also vitally needed in weaving and telling a renewed narrative, if it is not to be dead on arrival.

So, for the fresh voices, let the search begin.

Iniuro Wills, a lawyer, is the Bayelsa State Commissioner of Environment. He wrote this contribution for London Memorial for Ken Saro-Wiwa and Oronto Douglas.

The opinions contained in this article are solely those of the author.