by Crystal M. Hayes

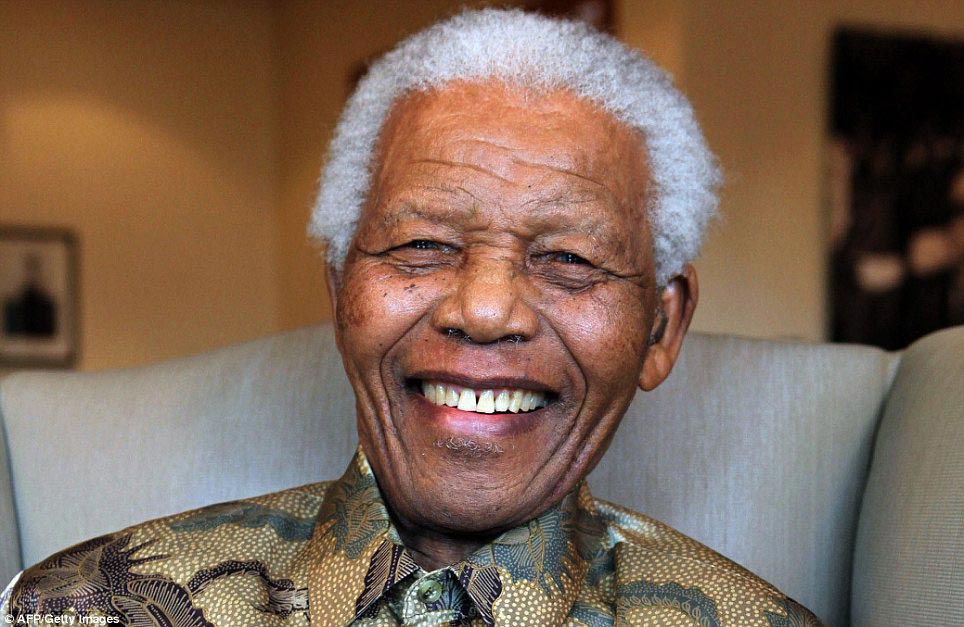

The death of Nelson Mandela, or Madiba as he is commonly called in South Africa, showed me that the world loved the idea of Mandela far more than his actual ideas.

When the news first broke that President Mandela was gone, it reverberated throughout the world. Facebook mourners swiftly, lovingly responded with new Mandela avatars and favorite quotes. Twitter memorialized Mandela with #RIPNelsonMandela hashtags trending worldwide. An editorial in The New York Times eloquently declared, “Nelson Mandela…fully deserved the legendary stature he enjoyed around the world for the last quarter-century of his life. He was one of the most extraordinary liberation leaders Africa, or any other continent, ever produced. Not only did he lead his people to triumph over the deeply entrenched system of apartheid that enforced racial segregation in every area of South African life; he achieved this victory without the blood bath so many had predicted and feared.”

Since June 2013 we all knew Mandela was gravely ill and that it was only a matter of time before he would no longer be with us. This fact didn’t make the news of his passing any less shocking. We were all impacted and moved to contemplate this amazing life. This was no less true for me. This past spring, I had the honor of visiting South Africa on an academic fellowship to design a community based service learning project that I developed focused on ending violence against women. My college-aged daughter was studying there at the time as well. I felt an overwhelming sense of pride and joy visiting the country that gave birth to Mandela and one of the most important freedom movements of our time. I could not contain my tears when the pilot announced we were flying over Robben Island on our way to Cape Town. That I was sharing my first South African journey with my daughter, made the trip even more meaningful.

Months later, back in my North Carolina home watching the news of Madiba’s passing unfold, my quiet reflection on the man, the movement, and the work, did not last long enough. Within hours of the death announcement, I watched as Twitterers, television news pundits, and politicians flattened his deeply complicated legacy rather than plumb the ninety-five year archive to honor the ways he challenged us to be more brave, loving—more fully human. Suddenly, everyone wanted to claim him. There are as many people today boasting that they were an anti-apartheid activist (who’s pro-apartheid anyway?!) as there are those claiming they marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. I am sure if both men were alive today, they’d be humored by how beloved they have become, and troubled by how far some representations of them are from their core beliefs and practices.

I don’t doubt that many people are deeply moved by Mandela, and I don’t presume to dictate any one right way to mourn and commemorate. That said, it is painfully evident to me that it’s easier for us to wrap ourselves in the symbols of Mandela’s legacy without questioning its substance and making sacrifices to participate in the hard work required to end oppression in our community and the world.

What does it mean when we can watch President Obama tell us that we must “strive for a future that is worthy of his sacrifice” while not demanding that President Obama free all political prisoners right here in the United States? It’s more than ironic that some of the same nations that once referred to Mandela as a terrorist or seditious figure gave him a hero’s tribute at his memorial. One thing is indisputable: Mandela deserved all the accolades. He peacefully negotiated an end to the violent apartheid system from his prison cell, leading the healing of his beloved country. As the first democratically elected President of South Africa, Mandela shared power with former apartheid state leaders and oversaw constitutional reforms that triggered the beginnings of systemic change still unfolding today.

Let us take care not to deify Mandela, which he rejected. Deification removes the responsibilities of social action from all but an exclusive community of sainted, celebrity activists. Deification is, at its core, disempowering. It erases the contributions of the millions of people, spanning decades and walks of life, who make human rights revolutions such as that which occurred in South Africa possible. Deification dehumanizes. Instead of learning from Mandela how to love broadly and act daily, we place him on a pedestal so tall we can no longer see or hear him and are left instead, to await the next prophet. The elevation of singular male figures muffles the voices of Winnie Mandela and other South African daughters who faced down apartheid. Deification coincides with sanitization. Cornel West talks about the Santa Clausification of Dr. King. Instead of “Beyond Vietnam,” US citizens meet the King of a few “I Have a Dream” sound-bytes, shreds of the original message. In short, deification serves a divide and conquer mentality that separates us from our own ability to participate in the struggle, the beautiful struggle, of self and societal emancipation. If we are alienated from our own powers of self-emancipation, we cannot work to expand freedom and joy alongside others.

If we are to strive for a future worthy of Madiba’s past, as President Obama urged, we must intervene against the violence in our midst. In the US, that means demanding the release of political prisoners like my father, former Black Panther Party member, Robert Seth Hayes, who has been held well beyond his original sentence, in a prison cell 40 plus years with little to no end in sight. We disgrace instead of furthering Mandela’s legacy by allowing apartheid like “Stop and Frisk” policies that treat Black and Brown bodies in New York City, and as Michelle Alexander has shown-nationwide, as born criminal. We further institutionalize racism of the sort Mandela helped overturn when we allow public schools to subject money-poor, and disproportionately Black and Brown kids to mediocre curriculums and over-worked, under-prepared teachers who too often view them as threats to manage instead of lights to teach and learn from. We also disgrace Mandela’s legacy every time we remain silent when Islamophobia appears everywhere from dinner table conversations to drone attacks in Pakistan, to US military atrocities against civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan. We miss Mandela’s message when we are unable to discuss gun violence in our own communities.

If we truly want to honor Nelson Mandela, let us look for him in our own private reflections. Let us begin, if we have not done it before, to have our own courageous conversations about how to eliminate the racial divide in our own country. When we choose the manufactured symbolism of Nelson Mandela the great compromiser, we get a Disneyfied mask that denies us the joy of the more complicated, human and thus familiar, Madiba, a Marxist freedom fighter who wasn’t afraid to challenge governments worldwide. Mandela challenged all those who he believed to be in opposition to freedom and justice including the United States. For example, on the eve of the US invasion of Iraq, he said, “If there is a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America. They don’t care for human beings.”

As we return to work and our families after enjoying this holiday season, let’s remember that Christmas is a ripe time for choosing Madiba over a shadow that bears his name. The story that pervades the US and other Christian majority nations this time of year is, yes, about the birth of a prophet. However, it is also the story of a radical whose practices were closely akin to those of King and Mandela, a fact the new Catholic pontiff, Pope Francis, is re-popularizing. The Pope’s Christmas Day message spoke of the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem as directed at “every man or woman who keeps watch through the night, who hopes for a better world, who cares for others while humbly seeking to do his or her duty…God is peace: let us ask him to help us to be peacemakers each day, in our life, in our families, in our cities and nations.”

The personal embodiment of love that Jesus of Nazareth practiced was also practiced by Mandela. To be sure, love is responsibility, as Erich Fromm and bell hooks have discussed. It recognizes and responds to which goes against love. Or, to invoke Dr. King, “…justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.”

The Christmas story and New Years is also about a new beginning, symbolized in the baby Jesus and all newborns. Perhaps it is for this reason that the Lincoln administration chose Christmas, new year season to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which it did January 1, 1863. January 1st is also the death anniversary of Oscar Grant, the Bay area 23 year-old shot to death by transit police in 2009. Grant is in the company of other unarmed youths like Trayvon Martin and men like Amadou Diallo, murdered in police interactions where Black and Brown bodies appear devoid of 4th amendment and habeas corpus rights, treated guilty until proven innocent. This is exactly the sort of state violence and double standard Mandela fought against.

Correcting that which stands against love, the way Mandela and those who worked alongside him did, requires us to have uncomfortable conversations with those who would hijack his legacy in lieu of doing the work to end atrocities against humanity. Allowing their flattened, ahistorical portrayals to circulate unchallenged is unacceptable and dishonors Mandela and all the people of South Africa who gave their lives to end apartheid. It also denies us the three dimensional, technicolor human being he was and we are. Madiba deserves better. We all do.

Crystal M. Hayes is a college professor in North Carolina. She can be reached on Twitter @motherjustice. This article was published on KultureKritic.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.