During my second-year philosophy in December 1981 at Bigard Memorial Seminary, Philosophy Campus, Ikot-Ekpene (now, St. Joseph Major Seminary), I was privileged to have played one of the leading characters in Wole Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero”, staged by our Bigard Theatre (Dramatists) Group, then. I must confess, however, I did not grasp the full imports of that Soyinka’s Play then until many years later in my adult life. All the same, I was happy, Soyinka, as early as then, had warned me in that play, of the dangers inherent in the abuse of religion and spiritual powers for influence, personal, and political gains, its consequences on the congregation and larger society.

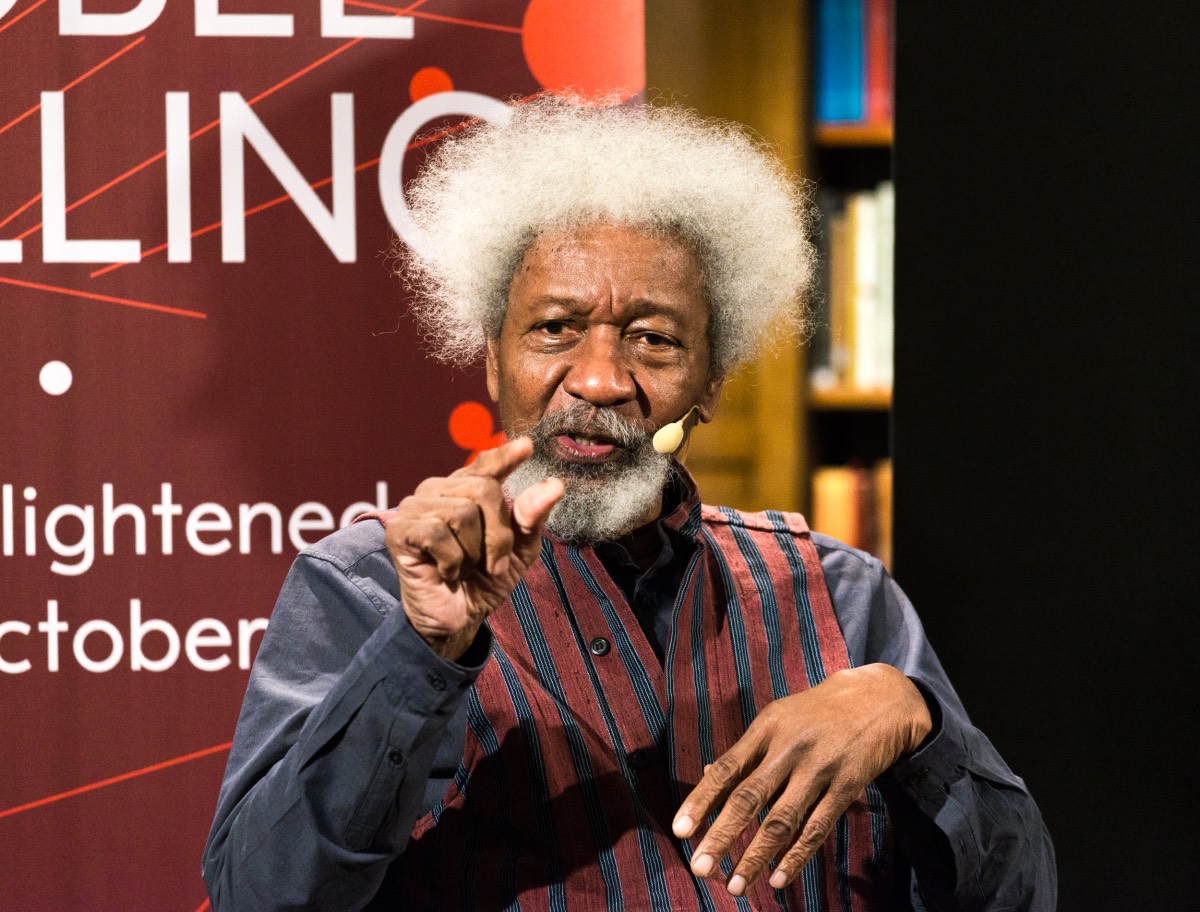

The present article is a follow-up to our previous one, “Achebe’s ‘Arrow of God’ and Politicisation of Religion in Nigeria.” Wole Soyinka, a Nigerian born African literary giant, social critic and Nobel laureate, discusses the same topic from the point of view of the principles of ‘African humanism’ and religious tolerance.

In Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero”, it is as if Brother Jero is the emerging “African Christianity’s equivalent of Nwulu in the “Arrow of God.” Brother Jero’s congregation, which operates along the Beach of Lagos, equally takes a similar role like that of Umuaro village-group in the “Arrow of God.” This is the general posture and texture of Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero.” The novel dramatizes in a more eloquent way, the emergence of most of today’s “Lagos based Neo-Pentecostalism and healing churches.” Not only in Lagos are they found, but across Nigeria and other parts of Africa and the world.

Again, if Achebe in his “Arrow of God”, dramatizes the politicisation of religion in the traditional and colonial African society, Wole Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero” is a classical example of how the politicisation is now transferred into Islam and Christianity with African slant. The same intrigues between priest-hero Nwulu and his village-group Umuaro, which we saw in Achebe’s “Arrow of God” for the Igbo society of the African Traditional Religion (ATR) during colonial-era, takes a more nuanced form and dangerous dimension in Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero.” Soyinka presents it as new features of emerging African type of Islam and Christianity.

Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero” and “Impunity of Religious Intolerance”

The themes of “Trials of Brother Jero” include romantic betrayal, religious hypocrisy; the skepticism over the use of religion. Much of the satire and irony in the “Trials of Brother Jero” comes from the contrast between a self-proclaimed “man of god” and the ordinary community life he finds himself. The play is technically a one act but has five scenes.

Brother Jero (full name: Jeroboam) is an evangelical prophet practicing along a large beach in Lagos, Nigeria. Despite his supposed holiness, he often takes advantage of people. While opportunistic and largely dishonest, Jero is also a product of the ignorant people around him. Jero understands what people want – money, respectability, political power – and he is willing to offer them compelling “prophecies” to reaffirm their deepest desires.

The play leaps forward to Jero standing in his “church” on the beach. He claims to be super successful and a self-made man. Despite all these seeming advantages, Jero is single; throughout the play, some comedic moments occur as he struggles against sexual impulses toward women, as well as their rebuffs.

Jero admits he doesn’t want any of his followers to be entirely absolved from their problems. When Chume asks for permission to beat his wife, Jero claims that that isn’t the right thing to do; the real reason for this advice is that Jero doesn’t want Chume to be so independent that he doesn’t require Jero’s services.

As time went further, Jero begins to think that he needs to have a good brand name and starts thinking of something ostentatious to call himself. Later in the play, he’ll settle on “the Immaculate Jero, Articulate Hero of Christ’s Crusade.”

Chume then joins Jero at the beach. Chume called sick into work. Jero is pleased that Chume found him on the beach, as he likes to appear as if he sleeps on the beach in an act of devotion.

Jero’s followers start to arrive on the beach. This includes two government workers, whom Jero enticed into his congregation by prophesizing that they will gain an even higher government post in future.

From an off-hand comment that Chume makes, Jero realizes that Amope is trying to collect a tax debt from him. To avoid having to pay anything, Jero finally tells Chume that God has told him it’s now okay to beat his wife.

Later that evening, Jero returns home to find Amope and Chume fighting in front of his house. Chume insists that they must go home; Amope refuses – she must collect money from Jero. The physical and verbal disagreement escalates, and neighbors start to gather to watch. Chume screams at Jero’s house that if he curses Chume, Amope will forgive all his debt. At this, Chume finally realizes that Jero only agreed to the wife-beating for his own benefit. Betrayal by his prophet and angry, Chume returns to the beach to punish Jero.

The final scene takes place at nightfall on the beach. Jero watches a young politician practice a speech he’ll give to his superiors. Scheming that Chume will no longer depend on him, Jero decides he needs more followers, and approaches the young man. He claims that unless the young man follows him, God will take his future political success. Helpless, the young man agrees.

Chume appears on stage muttering to himself. He believes Amope and Jero are having an affair. He insists, and it’s implied that he soon will commit a violent act against Jero.

The young politician kneels in the sand as Jero begins the conversion. But then, Chume bursts back onto the scene wielding a dulled sword; Amope accompanies him, and together they chase Jero. When the young politician opens his eyes again, Jero has disappeared. He interprets this as a sure sign that Jero is/was a man of God.

Once the scene calms down, Jero tells the audience what happened next. The politician started telling everyone that God whisked away Jero; he prays that the prophet will return. The politician is asleep on stage. Jero says that when he wakes up, he will tell him that Chume is an agent of Satan and must be locked up in a mental hospital. He throws a pebble at the young man, who wakes up and exclaims, “Master!”

The Ambivalence of Religion as Force for Peace and Intolerance and Manipulation

Apart from being a literary giant, Soyinka is a great advocate of ‘social change’ based on African humanism and religious tolerance:

“The spirituality of the black continent, as attested, for instance, in the religion of the orisa, abhors such principles of coercion or exclusion, and recognizes all manifestations of spiritual urgings as attributes of the complex disposition of godhead. Tolerance is synonymous with spirituality of the black continent, intolerance anathema.” – Wole Soyinka, “Burden of Memory”, 48 (1999).

The above quotation is from a Collection of Soyinka’s lectures delivered at Harvard University, titled, “Burden of Memory, The Muse of Forgiveness” (1997-1999). Here, Soyinka aligned himself with the “social vision” transmitted in African religion that he claims to be characterized by tolerance. In his seminal satirical play, under discussion, “The Trials of Brother Jero”, which was first performed in Ibadan in 1960, when he was only 26 years old, Soyinka was suspicious toward religion, particularly Islam and Christianity.

For Soyinka, these two “foreign” religions in Africa (Islam and Christianity), instead of making most of their talents or helping society, their brains were wrapped and shriveled up, which increased the superstitious nature of many middle and working-class Nigerians. While supportive of spirituality, Soyinka is against using religion for social, economic, moral, or political advantage. Soyinka received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986.

The ambivalence of religion as force for peace and at the same time easy for manipulation by some bad elements in the society to cause bad leadership, violence and conflicts as well as manipulate people, is what we have not been able to tame in Nigeria, Wole Soyinka would say! In a multi-cultural, multi-religious and multi-ethnic Nigeria, favoritism of one religion over and above others destroys the very foundation of the country itself as a nation state.

Just as Achebe did in “Arrow of God”, Soyinka also emphasizes the importance of multiplicity of centers of power, relationality, flexibility, respect for human person, as well as the necessity for religious tolerance that Nigeria must not ignore in its present-day predicament as a nation state.

Apart from the “Trials of Brother Jero”, another interesting work is Soyinka’s acknowledgement lecture of the Nobel Prize in literature, where he took issues with what he called “the exclusivist monotheism of Western Christianity that denigrated African religious values.”

Soyinka also discusses the politicisation of religion (Islam and Boko Haram) in Nigerian politics in a lecture he delivered on October 2014 at Waston Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University. The lecture was titled, “Hatched from the Egg of Impunity: A Fowl Called Boko Haram.”

Soyinka analyzes the current reign of impunity, religious intolerance and violence in Nigeria. Implied here is the disturbing reality that Nigeria, a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic and multi-religious nation state is notoriously operating an exclusivist, and an absolute federal, unitary system of government, controlled mainly by one ethno-religious group from the Northern part of the country. The present federal government of President Buhari, which is notoriously lopsided, is a case in point.

Because of this unjust situation, the political gatekeepers of Nigeria have continued to maintain their hold on power through impunity of all kinds, which includes, ‘hatching Boko Haram and Fulani killer-herdsmen’, and allowing them to continue unhindered, to unleash terror on the rest of the country, especially, Christians and indigenous populations of the Middle belt and Southern States of Nigeria.

Next, is Soyinka’s world most acclaimed masterpiece cited above, “The Burden of Memory, the Muse of Forgiveness, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute” (1999). “The Burden of Memory” consists of three lectures originally delivered at Harvard in 1997. The central concern in them is the question of how historic wrongs might be righted, the focus being on the terrible injustice the people of Africa have been subjected to: slavery, colonialism, apartheid, post-colonial misrule and dictatorship as well as the neo-colonial project.

Very interesting also is Soyinka’s article on Orisa (Yoruba) religion, titled, “The Tolerant Gods” (published in “Orisa Devotion as World Religion” (edited by J.O.K. Olupona and T. Rey (2008). He refuted Hegel’s claim (made in Lectures on the Philosophy of World History) that monotheism in Western philosophical categories is the symbol of civilization.

Soyinka, however, declared that the multiple spirits and mediators, like in the Yoruba orisa religion, were a more viable option. Soyinka’s claim for his Yoruba orisa religion is based on the existential experience of orisa cult as flexible, tolerant and respectful of the human person, as opposed to what he considers the “Christian and Islam totalizing and intolerant monotheistic order that denigrated other ways.”

Here Soyinka discusses the presence of “the multiple spirits and mediators, in the Yoruba orisa religion, as a more viable option.” Soyinka’s claim for his orisa religion is based on the existential experience of orisa cult as flexible, tolerant and respectful of the human person, as opposed to what he sees as the Western totalizing and intolerant monotheistic or exclusivist order that denigrated other ways.

“It is the profound humanism of the orisa that recommends it to a world in need of the elimination of conflict, since the main source of conflict between nations and among peoples is to be found as much in the struggle for economic resources as in the tendency toward the domination of ideas, be these secular or theological.” – (Soyinka, “Tolerant Gods”, 48).

The viewpoint of pioneer African theologian of Yoruba extraction, Bolaji Idowu, goes in the same direction. He believed that a renewed ATR is the only hope for the spiritual renovation of Africans.

Anyhow, Soyinka condemned the intolerance imbedded in the European (as well as Arab) spirituality and world vision upon which they had founded their colonial stronghold in Africa, especially, in the creation of modern African nation states. This, the West had done without consideration to the more tolerant and relational wisdom of African religion and spirituality.

According to Soyinka, exclusivism and monotheism imbedded in the Western and Arab spirituality and worldviews dominant in post-colonial Africa, do not promote the freedom and dignity of all humans. Thus, Soyinka aligned himself with the “social vision” transmitted in African religion that he claims, characterized African spirituality of relationality, and that he equally, claims was characterized by tolerance.

Both the Igbo wisdom saying, “Whenever something stands, something else will stand beside it”, and the Yoruba orisa religion option for tolerance and flexibility, are inspired by the same source. Both are inspired by the African philosophy of relationality (Ubuntu), “We are, therefore, I am” (cognatus ergo sum), as opposed to the individualistic Western (Descartes) philosophy, “cogito ergo sum” (I think, therefore, I am).

In African philosophy and traditional society, the value of interdependence through relationships based on shared equality and mutual respect comes high above that of individualism and exclusivism. In traditional African society, unilateral control or dominance from one center or by one ethno-religious group is anathema.

Some Critical Appraisal

However, some of Soyinka’s assumptions here need critical appraisal. Because while I may go for African philosophy of relationality and humanism, however, it is wrong to claim that the two religions that originated from the Near East – Christianity and Islam – are refactory. As I discussed in some of my earlier works, African Christianity practices lives and elaborates this relationship based on the flexibility of both ATR and Christianity. What Lamin Sanneh refers to as “cultural translatability” of Christianity and ATR.

Again, without downplaying the merit of Soyinka’s contribution, however, it is necessary to point out that his ‘universal condemnation of monotheistic religions’, did not take into consideration the fact that even African religion itself is a ‘monotheistic’ religion based on two principles – attributes of a monotheistic God. Africans’ attributes to God revolve around the two principles of creation and absoluteness.

For example, in Igbo religion and language, God is known as, a) “Chineke” (Creator-God (principle of creation); and b) “Chukwu” (Supreme Being, or High God (principle of absoluteness). In other words, the presence of multiple spirits as mediators in the divine hierarchy of African religion does not at all negate the monotheistic foundation of African religiosity and philosophy. Rather, it enhances the uniqueness of monotheistic God, already at work in the African religion, before the advent of Christianity and Islam in the continent.

I think that what is at stake in this case, is what Elochukwu Uzukwu rightly calls, the “Ontological Underpinnings of West African Religions.” The multiple tendencies in Igbo religion, for instance, draws attention to the underlying ontological principle of duality and plurality that is the basis for understanding being and religion in Africa. This understanding confirms the aphorism: “Whenever Something stands, Another comes to stand beside it”:

“Whenever something stands, something else will stand beside it” is repeated every so often as the ontological principle undergirding the understanding of the emergence of the Igbo human type. Igbo republicanism, their practice of direct democracy and their love for debate or palaver are derived from this principle. Duality or relationality is at the core of religion; it is at the core of the perception of Chukwu, the Supreme God.” – (E. Eugene Uzukwu, “God, Spirit, and Human Wholeness: Appropriating Faith and Culture in Western African Style”, (2012, p. 15).

This is, clearly seen in the founding myth of Nri (the most influential Igbo village-group, which we mentioned in our previous article on Achebe’s “Arrow of God.”):

“And what is more, Chukwu Himself in all His power and majesty, did not make the Igbo world by fiat. He held conversations with mankind. He talked with those archetypal men of Nri and Adama, and even enlisted their cooperation and good offices.” (Ibid. p. 17).

The philosophy behind this Nri myth is not unique to Igbo. The myth of pre-existence and having predestined course in life involving conversation with God and/or the deity bearing destiny are common among the Igbo and many other African societies.

Conclusion

In all, however, just like Achebe, Soyinka raises some issues pertinent for the protection and survival of human lives and properties of the indigenous ethnic populations and communities of the African people in Nigeria, as well as of Nigeria itself as a nation state. The relevance of Soyinka’s “Trials of Brother Jero”, is simple:

The Nobel Laureate, in his own literary style and methodology, is telling us that it is high time we take “a second look” against the politicisation of religion in Nigeria, and of why Nigeria as a nation state is in dire need of renegotiation. A renegotiation through referendum for self-determination of its diverse ethnic-nationalities or geopolitical regions, to address its faulty foundation and dangerous diversity.

The survival, security and protection of human lives and property must take precedence over the political interest or agenda of any nation, individual or group. The sacredness and inviolability of human lives comes first before any other interest of any nation state worth its name. Putting a particular political interest of a nation state, group or individuals before that of human survival or security and protection of human lives in any society, is a grave mistake. This is the mistake the gatekeepers of the Nigerian State have been making and have continued to make.

The Nigerian State as presently constituted, is not more important than the lives of its citizens, individual or collective, it was established in the first place to protect. Nigeria ceases to exist as a nation state from the moment it can no longer guarantee the protection and security of lives and property of Nigerians. This, unfortunately, is the ugly situation Nigeria found itself today.

It is high time we tell ourselves the “naked truth” and do the needful, correct the wrongs of the past, to save lives and the ancestral lands of the indigenous ethnic communities and peoples of African descent, forcefully logged together as one nation state by the British though colonial fiat in 1914, and named Nigeria. It is high time we begin to put the survival, protection and security of human lives and human existence first, in our scheme of things in Nigeria, and throughout the African continent. ‘A stitch in time saves nine!’

Francis Anekwe Oborji is a Roman Catholic Priest. He lives in Rome where he is a Professor of missiology (mission theology) in a Pontifical University. He runs a column on The Trent. He can be reached by email HERE.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.