by Arisa Cox

I was 24 years old. I was working at a now-defunct TV station in Ottawa and had just been promoted to entertainment/weather anchor for the evening and nightly news.

I hadn’t wanted to return to the often soul-destroying intensity of daily news after a year of reality TV in Toronto. But news is where I started my career in TV, cutting my teeth reporting local news for CJOH-TV during my third year as a Journalism major at Carleton University.

And though I had been enjoying my semi-obscure job as a creative producer at a different local TV channel, I was young, and the $17,000 raise offered to promote me back into news was hard to refuse. In the end, I had a blast. The staff was young, energetic and we got no sleep but worked really hard and made lifelong friendships doing it.

After the three-month probationary period was up, I had a customary performance review with the news executive. And the bomb dropped.

“You’ve worn your hair straight from time to time, we’d like you to wear it straight on the show.” I could feel the heat rising in my body. Ears buzzing.

“I’m not interested,” I replied without a beat. I was told the request wasn’t optional “if I wanted to keep my job.”

I wasn’t clutching my pearls, I was seething.

I remember raging to my mother over the phone right afterwards, floored that a middle-aged white dude had the balls to tell me, a modern black woman, in a country as diverse as Canada, how to wear my hair. My stubborn streak exploded. I didn’t care about corporate desires for me or my appearance. My hair — and all the identity and self-worth and cultural baggage attached to it — was not up for debate. I refused to allow my image to be controlled in some boardroom that I was not also in.

What those not in the film/TV industry often don’t know is that there is a built in clause in many on-air contracts that puts control of personal appearance in the hands of the employers. But just as my managers had a contractual right to demand I change my hair, I had also had a right to find a new job.

Which is the advice my wise mum gave me. She suggested I take that furious energy and put it into a job search. Canada’s media industry was small, after all. Both parties would benefit from saying I was simply moving onto another opportunity. By the end of the week, I had a new job that would move me back home to Toronto that was better paid and at one of the most diverse places I’ve ever had the pleasure of working at. I couldn’t have planned it better myself.

But I’m one of the lucky ones. Requests to wear processed hair for on-camera work is more common than you think — and not everyone is able to walk away from a job so easily. Sometimes the work is so great a journalist or performer must swallow their pride and surrender, no matter how irritating it may be. And it’s definitely not exclusive to black women.

The pressure for on-air types to go blond is well documented, and long hair is even better, since short hair tests poorly, or so the conventional wisdom goes. Remember when Keri Russell chopped off her signature curly mane during the Felicity years? Outrage! Ratings free fall! Chaos! And applause from me.

Like the vast majority of women, I can track my life story through my hair. Every different hair style or colour is a milestone that we can recall with ease — the significance being not so much the hairstyle, but how it made us feel. But for black women, our personal hair journeys have an additional layer of complication. Our hair is farthest from the European standard of beauty that you can get.

Until the Black is Beautiful movement of the 1960s when afros began to appear in earnest as a symbol of pride, every black woman’s right of passage was getting a perm. For those in the dark — that means using a highly toxic compound to chemically straighten kinky hair. You would still have to endure an hour of blow-drying and hot iron action after washing it, and be allergic to rain and swimming pools, but that’s the tradeoff. As a teenager, I tried it too. The goal is “good hair” — hair that moves, that shifts in the wind. To have natural or nappy hair meant looking like a slave.

Luckily, my Trinidadian-born parents — my mother with “good hair” and my father with long dreadlocks — had both worn afros in their pasts. They had long fostered my confidence in my smarts over my appearance, which was lucky, because my ugly duckling years were not kind. But being an outsider builds character. You learn to see not fitting in as standing out. And it frees you from traditional rules, especially those of the bajillion-dollar beauty industry. So I’ve tried it all. Braids until I was 16. Long and straight at 18. The afro came in at 22. At 25 it was short and mostly blond, at 31 the fern was much bigger and back to black to match my daughter.

By 2014, natural hair had made a massive comeback. Now there is an alternative theory that women who feel forced to wear long straight weaves are the slaves now to an ideal of beauty it is impossible for us to naturally attain. The head nod that we afroed women and men shared 15 years ago as strangers hardly exists now, in Toronto anyway, since there are so many of us. And we are all grateful for Angela Davis and Diana Ross and Pam Grier — the famous afros that came long before us.

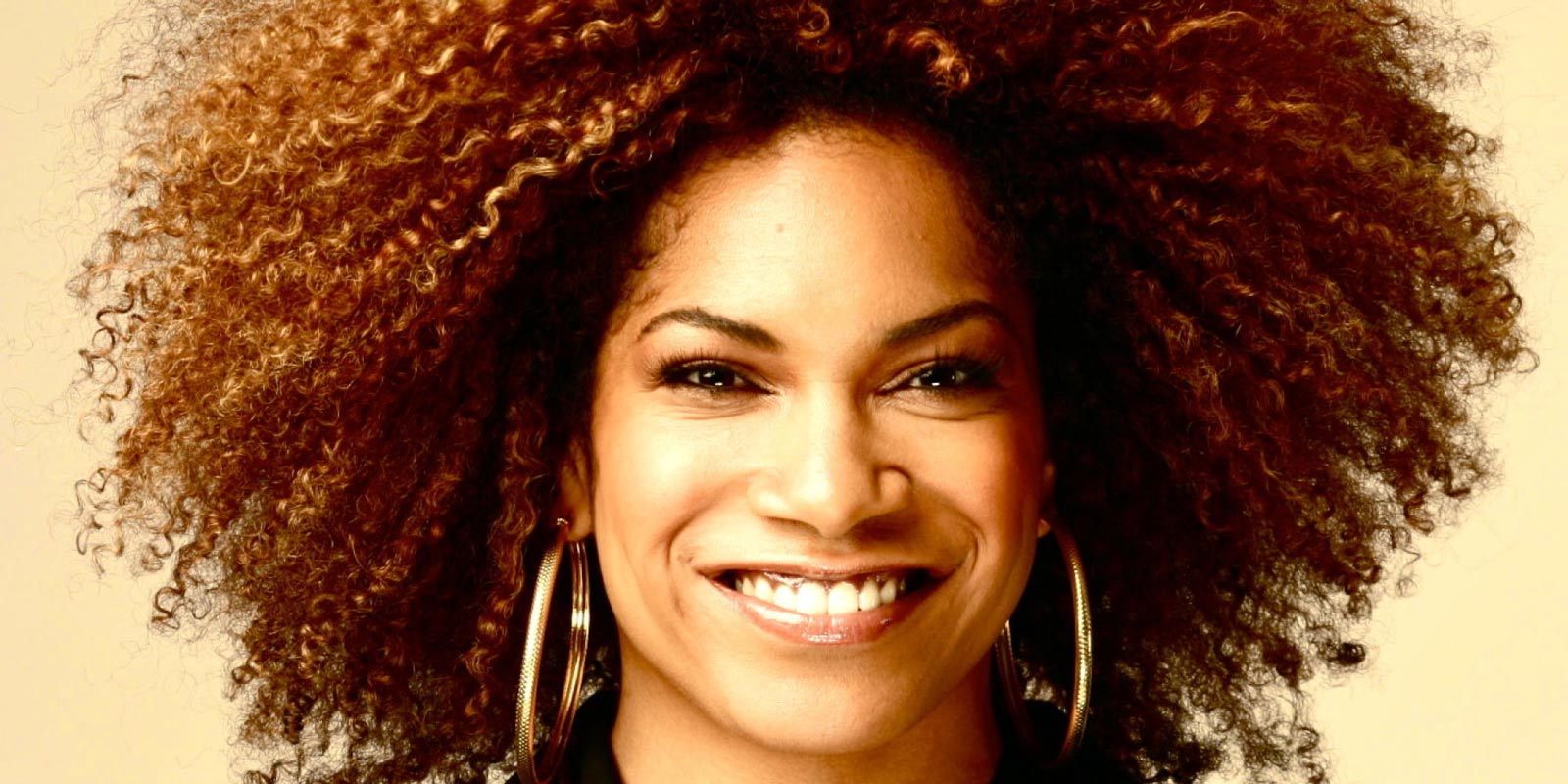

Working on Big Brother Canada has been a bit of a big deal for the natural hair scene as well. With so many international fans of our show, I have heard more than once that my hairstyle has been inspirational for many women and their daughters — struggling to fight the tide of weaved-out pop stars and celebrities. It’s humbling.

But reality exists in the grey areas. There’s Beyonce, but there’s also Lauryn Hill. Not all black women who wear straight hair are self-hating, just as not all black women who wear natural hair like afros, twists and dreadlocks have transcended vanity. Any woman should feel the freedom to wear whatever hair makes her feel good. It takes all kinds, and self-esteem as it relates to our hair comes in many forms. Most women are on a never-ending quest to find the hair that perfectly expresses who they are at that moment in time. We live in a visual, often superficial world, and we can’t see personality from across the room. But we can see hair.

I will never forget that breakthrough moment when my fabulous hair stylist Romeo Lewis said: “You know if you layer your hair, you can probably wear it curly all the time.” Sweeter words were never spoken. I have never looked back, and my hair remained a positive for the rest of my career in television.

People want to touch it, people want to understand it, people ask me questions about it on Twitter. It’s simple for me — I rock this hair because it’s low maintenance, because it’s a nod to my ancestors, because it’s hard to forget, because it feels like a celebration, like who I am on the inside showing up on the outside.

It’s all a matter of perspective. I am not a size two, I don’t have big boobs and I don’t have long hair that blows in the wind. But I do have a wicked sense of humour, curiosity for days, a big laugh and BIG HAIR.

So I didn’t lose my job. I won a sense of self-respect. I love a happy ending.

Arisa Cox is The Host of Big Brother Canada. This article previously appeared in the Toronto Star.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.