[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he criminal justice system is, broadly speaking, a set of agencies (police, courts and prisons) and processes established by government to control crime and penalise criminals. The Nigerian penal process, from being apprehended by the police, through court proceedings, to eventual imprisonment, is often described as ineffective, inefficient and inherently corrupt. In fact, research evidence suggests that as a consequence, there are many inmates who have no reason to be in prison in the first place.

There has been extensive research on the issue and many well-articulated arguments by legal experts for a holistic reform of our criminal justice system. If you’re interested, I find a good starting point is the policy paper by Tosin Osasona (Time to Reform Nigeria’s Criminal Justice System, Journal of Law and Criminal Justice, December 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 73-79). For this article however, I’ve chosen to focus on imprisonment and the need to reform the offender rehabilitation process in Nigeria.

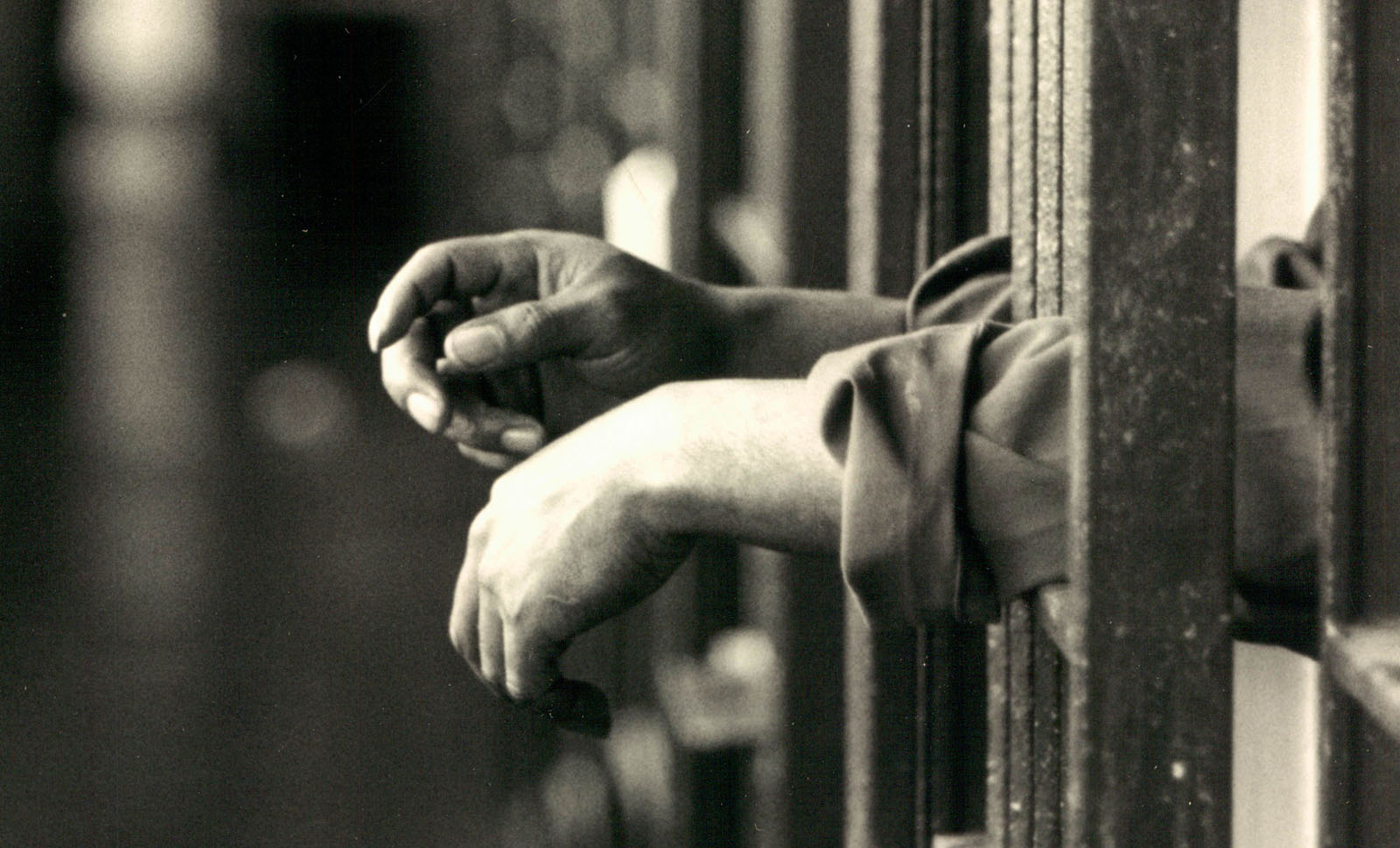

For the poor Nigerian, essentially most Nigerians, the justice system is a hazard. Poverty is that thin line between freedom and incarceration. It is unlikely that influential members of the society are locked up without convictions and subjected to the dehumanising conditions of the Nigerian prison environment. This class of Nigerians have access to good lawyers with expertise in frustrating trials and negotiating plea bargains. Woe betide you if you can’t afford one. The price for poverty here is ‘awaiting conviction’.

According to the Nigerian Prisons Service (NPS), there are 240 prisons across the country with a combined capacity of 50,777. The total inmate population reported was 57,121 as at October 2014. As a side note, with a Nigerian population of over 170 million people, I find the NPS figures dubious at best. The UK with less than a third of our population reported over 85,000 inmates in the same year. The US reported over 1.5 million (yes it’s the highest in the world but you get the point).

The NPS also reported that almost 70% (39,577) of the Nigerian inmates were listed as awaiting conviction! As alarming as it sounds, it may be much worse. These figures give the impression that their trials have reached an advanced stage. A large proportion of them may be awaiting trial i.e. those who have had no more than their plea taken, been refused bail and have remanded in prison custody for an indefinite period. Minna old prison is a good example with 385 inmates awaiting trial out of a total prison population of 467.

Imagine the impact of imprisonment on an individual who is there indefinitely merely because they couldn’t pay a fine. We are talking about Nigerian prisons that have been described as hell on earth. They are not designed for rehabilitation. They are overcrowded, dilapidated and outrageously inhumane. The effect is that prison sentences, even for the most trifling of offences, turn out to be excessively punitive, much harsher than the law intended, and too dehumanising to expect any rehabilitative effect.

The prison system should not just be punitive. It must also be correctional. Prisons are designed to serve three main purposes; punishment (deterrence for both the offender and would-be offender), public protection (by isolating the threat from the public) and rehabilitation.

If the intention is to eventually release the offender back into the public, why are we running a system that essentially forces a low risk offender through a prison system that transforms them into hardened, desperate and potentially dangerous individuals, only to release them back into society, exposing the public to even greater risks of crime and violence than before the individual was incarcerated?

Releasing an inmate without proper rehabilitation endangers the public. This risk is amplified by the conditions of the Nigerian prisons where the inmates learn to fight (literally) for survival. I mean, fight for sleeping space on concrete floors, fight for their meagre rations, fight just to make it through incarceration. This inmate, now accustomed to survival by violence, is released into a hostile world where they are unwanted, destitute and unemployable (well more so than before). They are now social misfits in survival mode. They are highly likely to reoffend.

In some states, Chief Judges routinely take magistrates on prison visits to arbitrarily release inmates who have served longer prison terms while awaiting conviction than the maximum sentence allowable for their alleged crimes. These inmates are usually released without any family members present to receive them, given little or no funds and sent away with no arrangements for shelter. While their release is clearly justified, doing so without any reintegration plans underscores a grossly incompetent and irresponsible prison system.

One way to understand the effectiveness of the prison system is by tracking recidivism (or the rate of reoffending). That is, how many of those that have been through the criminal justice process in the past end up back in prison. To monitor this, we must keep records of convictions and be able to track new cases against conviction histories of the offenders in question. It appears these trends are not tracked. Certainly not for recidivism.

There is currently no offender management system in Nigeria. There is little or no sharing of offender information between prisons and courts across the country. The onus is therefore on the prosecution to prove previous conviction(s). It is not even clear how imprisonment is impacting crime rates in Nigeria. If this information is not tracked, what then is the policy driving our criminal justice system? It appears focused on deterrence and punishment. There is little or no scope for rehabilitation.

Offender management is a complex process. Even the UK, with an annual spend of between £9.5 and £13 billion over the last decade, reported in 2015 that about half of all those released from prison go on to reoffend within 12 months. It is worth noting that the UK has an Offender Rehabilitation Act to regulate the release, and supervision after release, of offenders. In a bid to drive down the rate of reoffending, the UK government embarked on a wide ranging transformation programme to restructure the way offenders are managed.

Medium and low risk offenders are now managed at the community level by 21 CRCs (community rehabilitation centres) spread across the country, allowing the National Probation Service to focus on supervising high risk offenders being released into the community. All offenders were previously managed by the National Probation Service. The current approach is executed in partnership with private and voluntary sector partners. It is still too early to tell how this new approach has impacted reoffending rates in the UK.

We need to rethink offender rehabilitation in Nigeria. It begins with a reform of the legal process that has left almost 40,000 Nigerians (according to NPS reports) unfairly incarcerated without convictions, some for well over the maximum sentences mandated for their alleged offences. Upon incarceration, the government assumes responsibility for the offender, both in the interest of the inmate and that of the public.

A feasible plan of action might be to:

- Regulate the process of prisoner rehabilitation and release. Yes, more regulation! Create a statutory body to manage/supervise the rehabilitation process in partnership with the Nigerian Prison Service.

- Formally engage the private sector and voluntary organisations (some of which are already actively involved in prisoner rehabilitation) to offer rehabilitation services both during incarceration and after release. This will help to ensure that prisoners released into the public are fit to re-enter the community, are mentored, sheltered and actively employed to reduce the incentive to reoffend.

- For a start, the rehabilitation service can be implemented at the state level. With private sector participation, this can be further extended to the local government level. It is certainly more effective and cheaper to supervise offenders at the community level. It allows for quicker reaction to mitigate the risk of re-offense, both in the interest of the offender and of the public.

- Set up a dedicated national service to hold and manage information about every single offender (for current and previous incarcerations). This also includes information for non-custodial sentences.

- Set up a system to facilitate the exchange of offender information between the national offender database and all rehabilitation centres across the nation. This will allow for better tracking and management of recidivism.

How do we fund all this? Mr President has recently signed a justice budget for N17 billion. Here’s an item for your shopping list Mr Justice Minister! As already noted above, major reforms are required to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the penal process to ensure only the appropriate individuals are incarcerated in the first place.

There also appears to be limited alternatives to imprisonment in the current criminal/penal codes. Even the most trivial offences lead to a custodial sentence. Maybe the courts can consider using fines, community service etc. as punishment for lesser offences. This is a recurring suggestion in all of the criminal justice reform papers I have read till date.

Our justice system must provide protection for both the public and the offender. Temporary incarceration without rehabilitation is irresponsible and endangers the public even further, instead of providing the protections for which the system exists.

Buchi Madu is a UK based consultant specialising in change management within public sector organisations. He currently manages the implementation of business readiness strategies at the UK’s department for Education in support of the government’s universal ‘academisation’ policy. He is an associate fellow of the Nigerian Leadership Initiative (NLI). He can be reached by email HERE and on Twitter @buchimadu. He runs a blog, buchimadu.com.

The opinion expressed in this article are solely those of the author.