In America, the perennial quest for beauty is an expensive one.

Every year, women spend billions of dollars in exchange for beautiful hair, luxurious eyelashes, and smooth, silky skin. Still, many of our culture’s most common beauty procedures were virtually nonexistent a century ago. The truth is, many of our expectations of feminine beauty were shaped in large part by modern advertisers. We’ve tracked the history behind some of the most common “flaws” that besiege the modern woman and the surprising stories behind their “cures.”

Here are seven insecurities women have been fed by marketers:

1. “Your natural hair color isn’t pretty enough.”

“Does she or doesn’t she?” asked the Clairol’s ad that launched a million home hair dye jobs. Indeed, the aggressive Clairol marketing campaign would trigger an explosion in sales. In the process, the percentage of women dying their hair would skyrocket from 7 percent in 1950 to more than 40 percent in the ’70s.

The ads showed everyday women reaping the benefits of more lustrous hair, a luxury that had long been exclusive to glamorous supermodels with professional dye jobs. The ads proclaimed, “If I have only one life, let me live it as a blonde.” Indeed, Clairol peddled the perfect yellow shade of the dye as a way to transform your life:

Clairol hair dye offered self-reinvention, in 20 minutes flat, particularly for women who didn’t want to reveal their true age or their gray roots:

Shirley Polykoff, the advertising writer behind Clairol’s goldmine ad campaign, described her plan as such: “For big success, we’d have to expand the market to gather in all those ladies who had become stoically resigned to [their gray hair]. This could only be accomplished by reawakening whatever dissatisfactions they may have had when they first spotted it.” Clairol did that with ads like, “How long has it been since your husband asked you out to dinner?” Nowadays, about 90 million women in the U.S. color their hair, according to a 2012 IBIS World Report.

2. “Your body hair is gross.”

Today, women in media are generally depicted sans body hair or mocked for daring to bare it. But surprisingly, from the 16th to the 19th century, most European and American women kept their body hair au naturel.

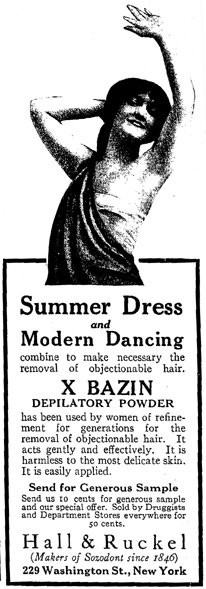

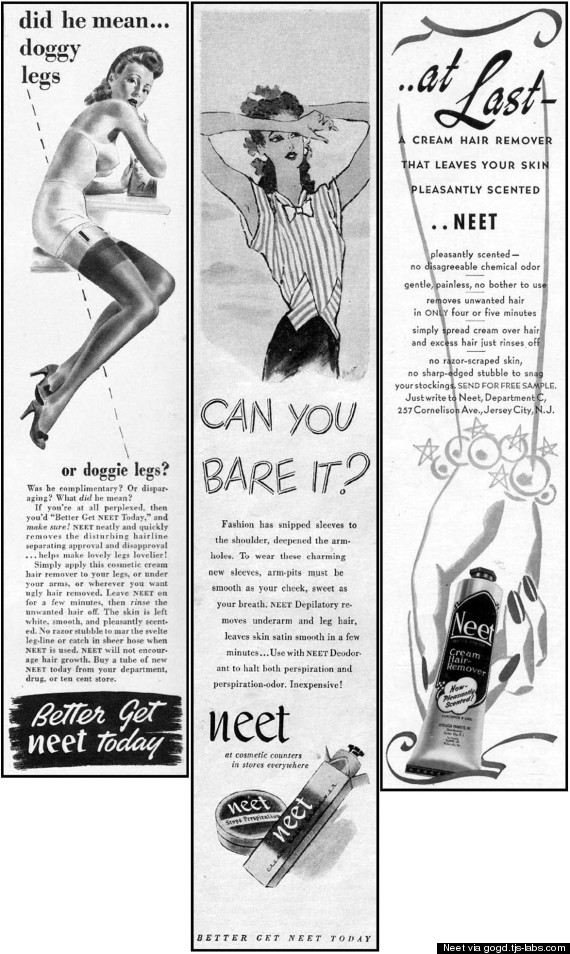

What changed? According to researcher Christine Hope, the answers lie in fashion and advertising. First, in 1915, came what Hope called an “assault on the underarm” — a burst of advertisements warning women that unsightly, unfeminine under-hair arm must be shaved to look “as smooth as the face.” Otherwise, no dancing for you:

Next, came an explosion of ads encouraging women to shave their legs to look more attractive in sheer stockings and fashionable swimwear. By the end of World War II, shaving had become an expectation for American women. Ads in the ’60s and ’70s continued espousing the “unfeminine” nature of body hair.

The bikini arrived on the fashion scene in 1946 and brought with it the next contested body hair territory: the bikini line. The Brazilian Wax was imported to the U.S. in the late ’80s and popularized by mainstream media in the ’90s.

Today, pubic hair removal is pretty much a staple amongst young American women: 80 percent of women between the ages of 18 and 34 remove at least some of it, and, according to research, many of them are motivated by the desire to conform to social norms or appear more feminine. Even now, hair-removal ads — like Veet’s recent “Don’t risk dudeness” campaign — target the same female-specific anxieties they did a century ago.

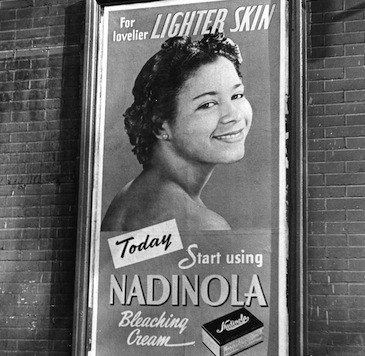

3. “Your skin is too dark.”

During the late-19th century and early-20th century, skin-lightening became increasingly popular among black women in America. Skin bleaching was seen as more than a beauty ritual — it was a symbolic way to progress in a prejudiced society, where lighter-skinned black people encountered comparatively better treatment. Advertisers exploited those prejudices in the beauty industry, promising women that they could “occupy higher positions socially and commercially, marry better, get along better” and be more beautiful with lighter skin. In this 1944 ad, lighter skin is equated with “lovelier” skin:

The actual products were seriously dangerous: Most contained the chemical hydroquinone, which is also used to develop photographs. (The chemical has been banned in Australia, the EU, and Japan, but remains legal in the U.S.)

During the ’60s and ’70s, the skin-lightening market dipped in popularity as the “Black is Beautiful” movement grew. The movement encouraged black people to embrace their natural features, rather than attempt to conform to white beauty norms. Cosmetic companies quickly softened their rhetoric, and the phrase “skin lightening” was changed to the somewhat more innocuous term “skin brightening.” The smiling 1962 ad below promises bright, light skin even on the rainiest day while neglecting to mention the possible side effect of mercury poisoning:

Today, skin lightening continues to be practiced around the world, with particular popularity in Africa, India and Pakistan. The annual global market is expected to reach $10 billion by 2015, though many of the products still come with serious health risks.

4. “Actually, your skin is too light.”

In the early 20th century, sunbathing became a popular doctor’s prescription for many illnesses. The supposed health benefits, coupled with a major boom in advertising, created the widespread belief that, as Harper’s Bazaar surmised in 1929: “If you haven’t a tanned look about you, you aren’t part of the rage of the moment.”

Soon after that declaration, beauty companies began selling specialized suntan lotions. Some researchers believe that, because the tanning fad created a new cosmetic market, it also provided a market incentive for the tan to remain an enduring American beauty expectation. And endure it did: In the 1970s, new health concerns about the risks of cancer from sunbathing did not end the craving for a tan — they just created more opportunities for the beauty industry to market new products that could promise protection or fake a “natural” tan that would have every beach bum staring:

The medical world continues to warn of the dangers of overexposure to the sun. The quest for the perfect golden tan hasn’t faded away — many people just choose to fake the effect. Since 2000, the self-tanning product manufacturing has experienced meteoric growth that is expected to continue over the next 5 years.

5. “Your cellulite’s an eyesore. It must be banished.”

Until 1830, large women were generally considered more beautiful and fashionable and master painters lauded their curves, cellulite and all. Since the mid-twentieth century, however, the ideal female form has become increasingly slender. Over the same period of time, cellulite was introduced and demonized as a major public enemy of the ideal female body.

In 1968, Vogue Magazine seized on the term, decreeing that, “Like a swift migrating fish, the word cellulite has suddenly crossed the Atlantic.” Some members of the medical world scoffed at the sudden cellulite anxiety that ensued, calling it an “an invented disease.” Whatever you call it, cellulite affects between 80 and 90 percent of women, and “fighting” it, as well as mocking it, have become marketable American obsessions. Being a female celebrity with any cellulite on your body is practically considered criminal:

In 2014, cellulite remains an unconquerable enemy, and women continue to spend big bucks on products that are often inadequately tested and ineffective in the long-term.

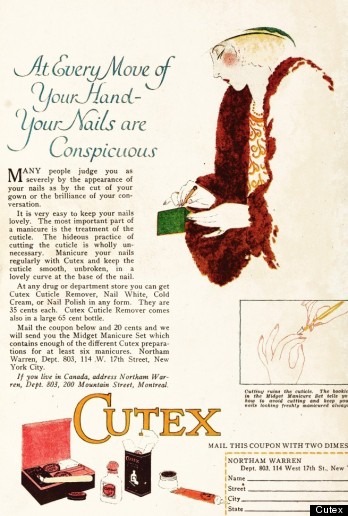

6. “Your unmanicured nails are unsightly.”

Northam Warren began producing what was generally considered to be the first fingernail cuticle remover and nail polish in 1911. He also kicked off an advertising campaign that would spawn the modern nail polish industry. Ads cautioned women about the embarrassment of having un-manicured fingers. Business exploded from $150,000 in 1916 to $2 million by 1920. Having manicured nails became a way to display wealth and elegance, proving that you were above “lowly” manual labor. And if you thought you could hide those unmanicured hands, this 1923 ad had news for you:

Image: Creative Commons, Cutex

The sales pitch worked. In 1912, only a quarter of women used products on their hands or fingernails — by 1936, three-quarters of women did so. During World War II, Cutex nail polish even appealed to women’s national pride:

Today, nail polish — and the services that go along with it — have become beauty staples for women. As of 2012, Americans spent a record $768 million on the stuff.

7. “Your eyelashes aren’t long enough.”

Historically, women darkened their lashes with everything from elderberries to resin, but mascara products didn’t emerge until the twentieth century when T.L. Williams founded Maybelline. The brand’s popular 10-cent mascara swept the nation. While makeup had once been considered immoral by some, Hollywood actresses made it glamorous. Women were promised the sultry eyelashes of their favorite actresses, as in this advertisement from a 1929 “Motion Picture” magazine:

As more mascara products emerged, companies began making numerous claims about the lengthening and volumizing effects of their products. Major cosmetic companies have come under fire for misleading advertising methods, like using false eyelashes on models.

Even so, the quest for longer lashes has grown into a full-fledged beauty and pharmaceutical market. As Nancy LeWinter, editorial director of OneStopPlus.com, told The Huffington Post: “Five years ago, the lashes you had were the lashes you had and you threw mascara on. Today, you’re getting extensions, you’re using Latisse, we’ve got the whole area of obsession over eyelashes!” ‘Cause hey, your eyelashes could always use another millimeter or two, right?